112

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

BERRIES.

Berries as a whole:

Popular Meaning................... 112

What a Berry is.................... 112

Blackberries:

Kittatinny......................... 123

Lawton, or New Rochelle.......... 122

New Rochelle, or Lawton.......... 122

Snyder............................. 133

Soil and Culture.................... 125

What they are...................... 122

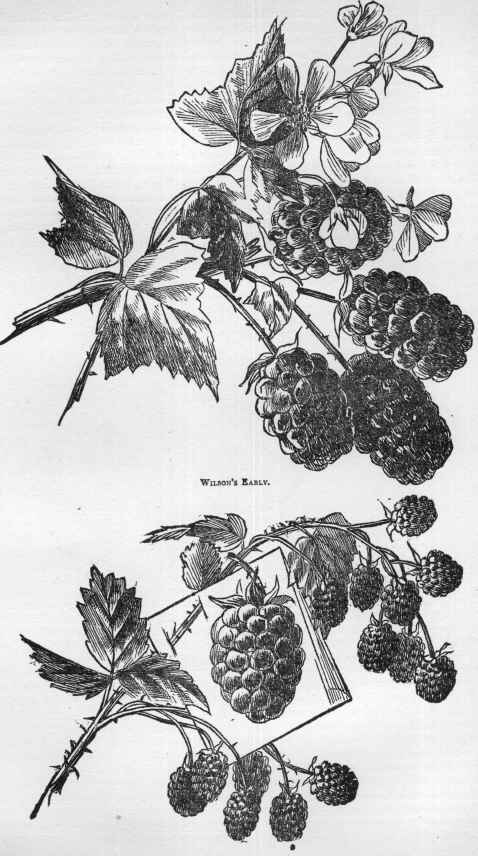

Wilson‘s Early..................... 123

Cranberries:

Cultivation......................... 129

Cape Cod Culture.................. 130

Description........................ 129

Name, the............ ............. 130

Results............................. 130

Uses................................ 130

Varieties........................... 129

Currants:

Black Currants..................... 127

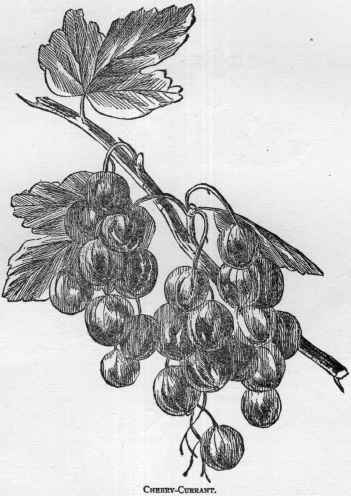

Cherry-Currant.................... 126

Choice and Preparation of Soil..... 127

Origin of Cultivated Varieties...... 125

Planting........................... 127

Red Dutch......................... 126

Versailles.......................... 127

Victoria............................ 127

White Dutch....................... 126

White Grape...................... 126

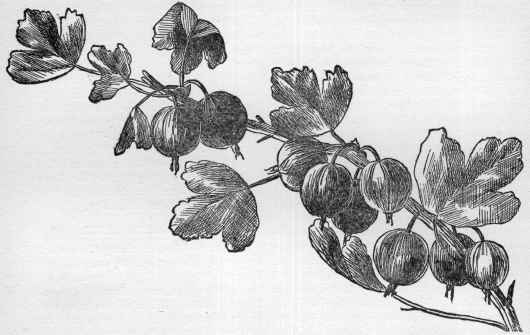

Gooseberries:

Cultivation......................... 128

Chester, or American Red......... 128

Description........................ 127

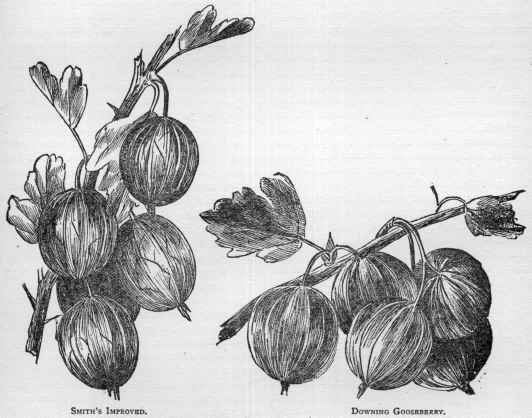

Downing .......................... 128

Foreign Varieties.................. 128

Hobbs’ Seedling................... 128

Houghton Seedling................. 128

Mountain Seedling................. 129

Pale Red........................... 129

Ribes Hirtellum.................... 128

Smith‘s Improved.................. 128

Raspberries:

Belle de Fontenay.................. 121

Black-Caps......................... 122

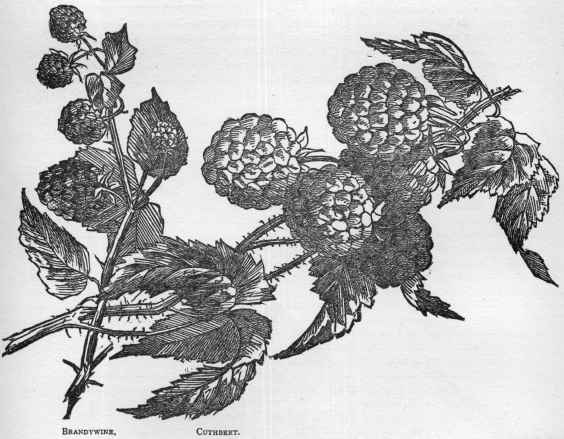

Brandywine........................ 122

Cuthbert........................... 122

Description......................... 118

Fastollf............................ 119

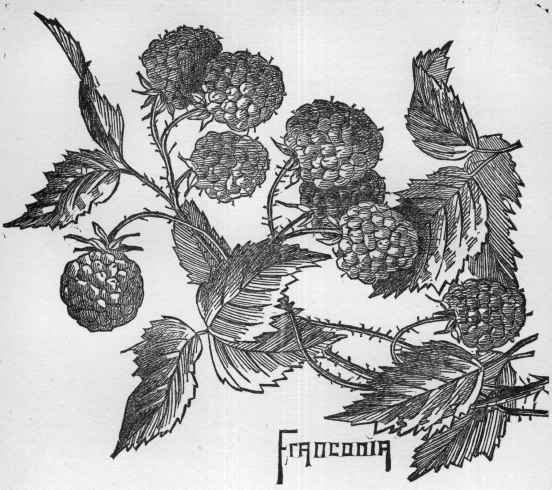

Franconia....... .................. 119

Hudson River Antwerp............ 119

Knevet‘s Giant..................... 119

Manures............................ 122

Native Red Species................ 118

Propagation........................ 122

Red Antwerp of England.......... 118

Soil and Culture.................... 122

Turner............................. 121

Strawberries:

Bad Planting...................... 116

Black Defiance..................... 115

Strawberries:

Charles Downing.................. 114

Crescent Seedling.................. 115

Description......................... 113

Different Methods of Cultivation... 117

Duchess............................ 115

Fragaria Chilensis.................. 113

Fragaria Virginiana................ 113

Freshening up Roots............... 116

Hill System........................ 117

Hovey’s Seedling.................. 113

Jucunda............................ 115

Manures............................ 118

Matted Bed System................ 117

Monarch of the West............... 114

Mulching.........................117

Narrow Row System............... 117

Neuman‘s Prolific.................. 116

Original Ancestor.................. 113

Origin of the Name................ 118

Planting and Setting...............116

President Wilder................... 115

Runners........................... 117

Seth Boyden........................ 115

Sharpless........................... 115

Shortening Roots.................. 116

Spring Cultivation................ 118

State of the Ground................ 116

Triomphe de Gand................. 115

Watering.......................... 117

Wilson‘s Albany.................... 113

What is a Berry ?— Perhaps the reader imagines

that he (or she—where is that epicene pronoun ?)

knows what a berry is. Listen : “ This term is

employed in botany to designate a description

of fruit more or less fleshy and juicy, and not

opening when ripe. The inner layers of the

pericarp are of a fleshy or succulent texture,

sometimes even consisting of mere cells filled

with juice, whilst the outer layers are harder, and

sometimes even woody. The seeds are immersed

in the pulp. A berry may be one-celled, or it

may be divided into a number of cells or com

partments, which, however, are united together

not merely in the axis, but from the axis to the

rind. It is a very common description of fruit,

and is found in many different natural families,

and both of exogenous and endogenous plants.

As examples may be mentioned the fruits of the

gooseberry, currant, vine, barberry, bilberry, bel

ladonna, arum, bryony, and asparagus, which, al

though agreeing in their structure, possess widely

different properties. Some of them, which are

regarded as more strictly berries, have the calyx

adherent to the ovary, and the placentas—from

which the seeds derive their nourishment—pa

rietal, that is, connected with the rind, as the

gooseberry and currant; others, as the grape,

have the ovary free, and the placentas in the

center of the fruit. The orange, and other fruits

of the same family, having a thick rind dotted

with numerous oil-glands, and quite distinct

from the pulp of the fruit, receive the name hes-

peridium; the fruit of the pomegranate, which is

very peculiar in the manner of its division into

cells, is also sometimes distinguished from berries

of the ordinary structure by the name balausta.

Fruits like that of the water-lily, which at first

contain a juicy pulp, and afterwards, when ripe,

are filled with a dry pith, are sometimes desig

nated berry-capsules. The gourds, also, which

have at first three to five. compartments, but

when ripe generally consist of only one compart

ment, are distinctively designated by the term

pepo, peponium, or pepontda, to which, however,

gourd may be considered equivalent.”

Popular Signification of the Word.—The term berry

is usually applied to several small fruits which

are not berries in the scientific sense, as the

Strawberry, which bears seeds (ackenia) on the

external surface of an enlarged and pulpy recep

tacle. So under the head of Berries in this book

the Strawberry is put; while, per contra, under

another head are placed Grapes, which although

scientifically berries, will be found under Fruit.

Neither grapes nor oranges partake of the ephe

meral and quickly perishable nature characteriz

ing what are in common parlance known as ber

ries.

The cultivation of berries and small fruits has

largely increased within the last few years, and in

berries. 113

most cases where it has been carried on judi

ciously in the vicinity of large markets, or at

remoter points under favorable freighting ar

rangements; the results have generally proved

successful in variety, quality and quantity.

There has been a steadily increasing demand for

this product, and farmers and fruit-growers who

send articles of good quality, and in good condi

tion to market, are sure to be well remunerated.

STRAWBERRIES.

What the Strawberry is.—The first place in any

list of “ berries” undoubtedly belongs to this old

friend. Not a berry proper, it is Fragaria; a

genus of plants of the natural order Rosaceœ, sub

order Roseœ, tribe Potentillzdœ, remarkable for

the manner in which the receptacle increases and

becomes succulent, so as to form what is popu

larly called the fruit; the proper fruit (botanical-

ly) being the small achenia which it bears upon

its surface. The genus differs from Potentilla

chiefly in having the receptacle succulent. The

calyx is 10-cleft, the segments alternately small

er; the petals are five; the style springs from

near the base of the carpel. All the species are

perennial herbaceous plants, throwing out run

ners to form new plants; and the leaves are

generally on long stalks, with three leaflets, deeply

toothed. One South American species has sim

ple leaves. In no genus are the species more

uncertain to which the cultivated kinds are to

be referred.

The Original Ancestor.—The common strawberry,

8

Fragaria Virginiana, which grows wild east of

the Rocky Mountains, is the ancestor of the end

less varieties of this berry, the raising of which

forms today so large an industry in many parts

of the United States.

Another species, called Fragaria Chi/en sis, grow

ing wild along the Pacific coast both in North

and South America, seems to flourish better in

Europe than with us. The European gardeners

are seeking to perfect it, but most of the choice

varieties have not succeeded when imported

here.

The Virginian strawberry is most remarkable

in its capacity for improvement, as all the present

varieties attest.

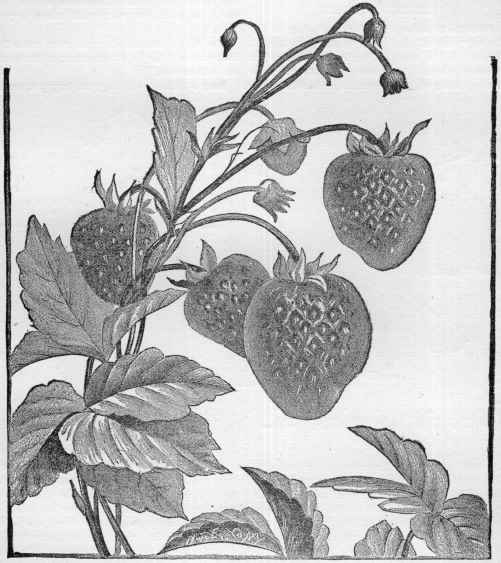

Hovey’s Seedling.—This great improvement on

the original wild strawberry was introduced in

1834 by C. M. Hovey, of Cambridge, Mass., was

the first precursor of a long line, and is still a

very fine variety. The vines are vigorous and

hardy, producing moderately large crops, and

the fruit is of the largest size and finely flavored.

It is well known all over the country. The leaves

are large, rather light green, and the fruit-stalk

long and erect. Fruit very large, roundish oval

or slightly conical, deep shining scarlet. Seeds

slightly imbedded. Flesh firm, with a rich, agree

able flavor. It ripens about the medium season,

or slightly later.

Wilson’s Albany.—About 1854, John Wilson, of

Albany, N. Y., introduced this variety, which

has since been more generally cultivated than

any other. The vine is very hardy and vigorous,

114 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

very productive, beginning to ripen its fruit early,

and continuing to the latest. Fruit large, broadly

conic, pointed. Color deep crimson. Flesh crim

son, tender, with a brisk acid flavor. In fact, it

is too acid. Mr. Bryant, in the Evening Post, in

1876, gave his opinion: “ Wilson‘s Albany is a

sour, crude berry which is not fully ripe when it

is red, and when perfectly ripe is too acid. When

it first makes its appearance in the market it has

a harsh flavor, and but little of the agreeable

aroma which distinguishes the finer kinds of

the berry. But the Wilson is a hardy berry;

bears transportation well; is exceedingly prolific;

qualities which give it great favor with the cul

tivator, but for which the consumer suffers.

We hope that the Wilsons, as soon as their

place can be supplied with a better berry, will

Seth Boyden Strawberry.

be banished from the market,’’ If people do not

demand a better variety, the cultivator will con

tinue to send to market a berry which carries

well, ripens early, and is most prolific.

Charles Downing.—Another variety which grows

well in all parts of the country, introduced by J.

S. Downer, Fairview, Ky. Plant very vigorous

and very productive. Fruit very large, nearly

regular, conical, deep scarlet. Seeds brown and

yellow, rather deep. Flesh quite firm, pink, juicy,

sweet and rich.

Monarch of the West.—This is a very highly

prized strawberry, raised by Jesse Brady, of

Piano, Ill. Plant vigorous, with large, pale

green leaves, moderately productive; a good va

riety for home use and a near market; requires

high cultivation and rich soil to produce large

BERRIES.

115

fruit abundantly and of good quality: should be

grown in hills or narrow rows. Fruit large,

sometimes very large, roundish conical, nearly

regular; a few of the early berries are coxcomb-

shape, and a little irregular; light scarlet; flesh

light red, rather soft, juicy, sprightly subacid,

rich: quality very good.

Seth Boyden.—(Newark, N. J.) Mr. H. Jerola-

man, of Hilton, N. J., writes in 1877 : “My yield

from one acre, planted chiefly with the Seth Boy-

den, was 327 bushels 15½ quarts, which were sold

for $1,386.21. A strict account was kept. Since

that time, I have been experimenting with Mr.

Durand‘s large berries, and have not done so

well. In 1878, I obtained $1181 from one acre,

one half planted with the Seth Boyden and the

Other with the Great American. The year of

1879 was my poorest. Nearly all my plants were

Great American and Beauty, and the yield was

121 bushels, selling for $728. The average cost

per acre, for growing, picking, marketing and

manure, is $350. I am not satisfied but that I

shall have to return to the old Seth Boyden in

order to keep taking the first State premiums, as

I have done for the past three years.”

Sharpless.—This large, showy strawberry ori

ginated with J. H. Sharpless, of Catawissa, Pa.;

very vigorous, with large dark green, coarsely

serrated and deeply veined leaves; very pro

ductive, and is best adapted to the hill system,

making large stools ; it also succeeds in narrow

rows. Fruit large to very large, variable in form,

from irregular coxcomb-shape to roundish coni

cal and oval; bright scarlet, somewhat glossy;

flesh light red, quite firm, moderately juicy, sweet,

rich and of very good flavor; medium to late in

ripening. Very promising, either for market or

family purposes.

Duchess.—This excellent early strawberry ori

ginated in the garden of D. H. Barnes, Pough-

keepsie, N. Y. Very vigorous, foliage of medium

size, dark green and healthy. Very productive ;

when grown in hills or narrow rows it stools and

makes large plants, thus saving the labor of re

planting. Fruit medium to large, roundish,

obtuse conical, regular in form, bright scarlet

or crimson; flesh light red, quite firm, juicy,

sprightly subacid, and of fine quality; one of the

earliest to ripen, and continues a long time for

an early variety; retains its size quite well to the

last; is valuable for early market, and also for

general use in the family. Dr. Thurber, of

the American Agriculturist, unhesitatingly pro

nounced this the best of fifty varieties in one of

Mr. Roe's specimen-beds.

Black Defiance.—One of the seedlings of E. W.

Durand, Irvington, N. J. Plant vigorous, with

dark green foliage, productive in heavy soils ;

requiring high culture in hills or narrow rows,

and removal of runners to obtain the fruit in

quantity and perfection. Fruit large, roundish,

obtuse conical, regular; color dark crimson;

flesh dark red, firm, juicy, sprightly and rich;

rather early, fine for the amateur, and seems a

good variety for shipment to an early market.

Triomphe de Gand.—A Belgian variety, which

appears to stand our climate, and produce more

crops in more localities than any other foreign

sort. The vines are vigorous, hardy, moderately

productive, and well suited to strong, clayey

soils, requiring high cultivation, and to be grown

in hills. Fruit large, roundish obtuse, sometimes

coxcomb-shape, bright rich red near the calyx,

almost greenish white at point, glossy as if var

nished ; seeds light yellow-brown, near surface;

flesh firm, white, a little hollow at core, juicy,

with a peculiar rich and agreeable flavor.

President Wilder.—Raised in 1860 by Hon. M.

P. Wilder, of Dorchester, Mass., from seed of

Hovey‘s Seedling, impregnated with La Con

stante Plant healthy, hardy, vigorous and very

productive. Fruit-stalk short, stout, erect.

Stands the heat of summer and cold of winter

uninjured. Fruit large to very large, roundish,

obtuse - conical, very regular, bright crimson-

scarlet. Seeds mostly yellow, near the surface.

Flesh very white, quite firm, juicy, sweet and

rich. Roe calls this “ President Wilder‘s superb

seedling.”

Crescent Seedling. — Originated with William

Parmelee, New Haven, Conn. Hardy, strong,

a vigorous grower and very productive. Leaves

of medium size, dark green; requires much

room to give good results ; ripens early and con

tinues late, holding its size tolerably well, and

although not of high flavor, its fair size, good

color and moderately firm flesh have given it a

near-market value. Fruit medium to large,

roundish conical, the first berries a little irreg

ular or uneven, bright scarlet; seeds yellow and

brown, near the surfaces. Requires less time and

attention than most varieties, and is well calcu

lated for those who cannot and will not give the

necessary labor to produce the better kinds.

Roe says it renders the laziest man in the land,

who has no strawberries, without excuse. One

of his beds yielded at the rate of 346 bushels to

the acre.

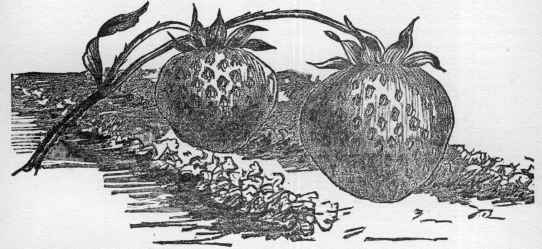

Jucunda.—A foreign variety, that, like some

others of its class, does extremely well in a few

localities under high cultivation. Plant moder

ately vigorous. Fruit large to very large, obtuse-

conical or coxcomb-flattened, bright light scar

let. Seeds mostly yellow. Flesh light pink,

moderately firm, sweet, not high flavor, often

hollow. So says Downing. Roe says: “ The

Jucunda is one of the most superb berries in ex

istence, and can be grown with great profit in

116 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

many localities. . . . During the past summer,

I had upon my wettest and stiffest land two

beds of Jucunda strawberries that yielded at the

rate of 190 bushels to the acre. The Jucunda

strawberry is especially adapted to heavy land

requiring drainage, and I think an enterprising

man in the vicinity of New York might so unite

them as to make a fortune.”

Neuman's Prolific, or the Charleston Berry, is the

great staple in the South, and the chief variety

for shipping. “ It is an aromatic berry, and

very attractive as it appears in our markets in

March and April, but is even harder and sourer

than any unripe Wilson. When fully matured

on the vine, it is grateful to those who like an

acid berry. Scarcely any other kind is planted

around Charleston and Savannah.”—Roe.

Planting and Setting.—Good plants deserve and

will repay careful setting and care. There is

some very favorable weather in early spring, in

which a plant is almost certain to grow even if

carelessly set out, but even then it does better

if properly treated. It is almost as easy to set

out a plant correctly as incorrectly. Excavate

a place large enough and deep enough to take

in the roots, expanded fan-like, their whole

length and circumference. Take the plant in

one hand, and with the other half fill the hole

with rich fine earth, and press it firmly against

the roots; then fill it evenly, and with both

hands press your weight on the soil all around

the plant, till the point from which the leaves

start is even with the ground. The plant must

be in the ground too firm to be lifted by the

leaves. Roe says : “ If a man uses brain and eye,

he can learn to work very rapidly. By one dex

terous movement, he scoops the excavation with

a trowel. By a second movement, he makes

the earth firm against the lower half of the

Jucunda Strawberry.

roots. By a third movement, he fills the exca

vation and settles the plant into its final posi

tion. One workman will often plant twice as

many as another, and not work any harder.

Negro women at Norfolk, Va., paid at fifty cents

per day, will often set two or three thousand.

Many Northern laborers, who ask more than

twice that sum, will not set half as many plants.

I have been told of one man who could set 1000

per hour. I should examine his work carefully,

however, in the fear that it was not well done.”

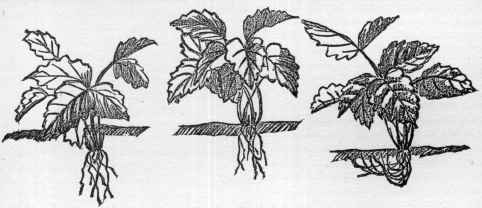

Bad Planting.—On the opposite page are three

illustrations of “ how not to do it.” In the first,

the plant is smothered and stifled by being set

too deep in the earth. In the second and third,

the roots are not given the chance for life they

need. All these might have been set out pro

perly in no more time than was taken to set

them out improperly.

State of the Ground.—This should be made as

nearly level as possible, and equally removed

from a dry lumpy condition, and from one

where the water will not readily drain off. Plant

in moist, freshly stirred earth, and never when

the ground is wet and sticky, unless at the be

ginning of what threatens to be a long storm.

Shortening Roots.—In the spring, roots should

be shortened one third, which excites a rapid

growth of new rootlets, and consequently of the

plants. But later in the season, the plants not

having such an abundance of roots, it is best not

to cut them.

Freshening up Roots.—Sometimes, in along jour

ney, roots get black and sour, and perhaps

moldy. In such case, wash them in clean tepid

water, trim carefully, removing the darkened,

withered ends, set out the plant, treat it with a

little bone-meal, and water it. In warm weather

keep the ground moist till rain comes.

BERRIES.

117

Watering.—The ground should be kept moist

continually, day and night. Give the plant

what it needs till it is able to take care of itself.

Shade it if necessary. The conditions of its

healthy life are coolness, shade and moisture.

Different Methods of Cultivation.—One well-known

plan is the Matted-bed system. The ground be

tween the rows is cultivated and kept clean

during spring and early summer. But the fast-

increasing runners prevent thorough cultivation,

and by winter the entire ground is covered with

plants, and in that condition mulched. In the

spring, the coarsest of the covering is raked

off, and a path made between the rows, to be

afterwards used by the pickers. Under this sys

tem the first crop is usually the best, but the

land often becomes so foul that it does not pay

to keep up the beds the second year. Often two

crops are taken, and then some other crop

alternated before going back to strawberries.

This system sometimes produces fair results, but

is untrustworthy and slovenly. Under it the

farmer has berries a few days where he should

have a few weeks, and his entire crop ripens at

once, perhaps in an overstocked market. It is

no method for a garden, as the hoe and fork

cannot be used among plants sodded together.

There are some modifications of the system, but

they all seem unsatisfactory and slovenly.

Another plan of cultivation is the Hill system.

In this the plants are set out say three feet

apart, and treated like hills of corn, except that

the ground should be level. They are often so

arranged that the cultivator can pass between

them each way. But there are grave objections

to this method. A great deal of ground is wasted,

and the white grub has a chance to do his de

structive work. The labor of mulching, where

so much of the ground is unoccupied, is great.

In small garden-plots this system often works

well. There is opportunity to eradicate weeds,

" How not to do it."

to keep the soil mellow and open, and so moist,

and the plants make great bushy crowns, cover

ing the whole space. In the South, this seems

the best system. There the plants are set in the

summer and autumn, and the crop is taken from

them the next spring. The plants are there set

only one foot apart in the rows, and the runners

can be kept down, and each separate plant stimu

lated to do its best.

The third plan of cultivation is the Narrow-row

system, in which the plants are set one foot from

each other in line, and in rows two and a half or

three feet apart, and are not allowed to make

runners. In a good soil they will touch each

other, and make a continuous row, after a year‘s

growth. Between the rows the cultivator can

be carefully run, and the plants from the rows

kept clear of weeds by hand and a small fork.

The ground is thus occupied to the utmost

profitable extent, the berries have access to air

and light, and the beds can be readily mulched.

If necessary, the ground can be easily irrigated,

and the white grub extirpated.

Runners.—Each plant strives to propagate itself;

but if allowed to do so, and in the degree to

which it is allowed, it lessens its own vitality

and power to produce berries the following

season. Remove the runners, and the life of the

plant is concentrated on foliage and fruit. Such

a plant has abounding life, works evenly and

steadily, and perfects its last berry. Rows under

this system have been in bearing seven weeks.

Unless plants are very strong, and set out very

early, fruiting the same year is always dangerous

and often fatal. If berries are wanted in a year,

the plants should be set out in summer or

autumn.

Mulching.—As freezing weather comes on, plants

should be protected with leaves or straw, or

light strawy horse-manure, sufficiently fer

mented to kill the grass-seeds. The plants must

118 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

not be smothered, and yet must be protected.

Watch them during the winter, recover where

washed away, and drain off all puddles. As the

weather softens in early spring begin to push

back the covering, and let in air.

Spring Cultivation.—Edward P. Roe, in his inter

esting and instructive Success with Small Fruits,

recommends “spring cultivation, if done pro

perly and sufficiently early. Even where the soil

has been left mellow by fall cultivation, the beat

ing rains and the weight of melting snows pack

the earth. All loamy land settles and tends to

grow hard after the frost leaves it. While the

mulch checks this tendency, it cannot wholly

prevent it. As a matter of fact, the spaces

between the rows are seldom thoroughly loosened

late in the fall. The mulch too often is scat

tered over a comparatively hard surface, which

by the following June has become so solid as to

suffer disastrously from drought in a blossom

ing and bearing season. I have seen well-

mulched fields with their plants faltering and

wilting, unable to mature the crop because the

ground had become so hard that an ordinary

shower could make but little impression. More

over, even if kept moist by the mulch, land long

shielded from sun and air tends to become sour,

heavy, and devoid of that life which gives

vitality and vigor to the plant. The winter

mulch need not be laboriously raked from the

garden-bed field, and then carted back again.

Begin on one side of a plantation and rake

toward the other, until three or four rows and

the spaces between them are bare; then fork the

spaces or run the cultivator—often the subsoil

plow—deeply through them, and then immedi

ately, before the moist, newly made surface

dries, rake the winter mulch back into its place

as a summer mulch. Then take another strip

and treat it in like manner, until the generous

impulse of spring air and sunshine has been

given to the soil of the entire plantation.”

Manures.—The same author writes : “ Never

seek to stimulate with plaster or lime, directly.

Other plants’ meat is the strawberry's poison in

respect to the immediate action of these two

agents. Horse-manure composted with muck,

vegetable mold, wood-ashes, bone-meal, and, best

of all, the product of the cow-stable, if thoroughly

decayed and incorporated with the soil, will

probably give the largest strawberries that can be

grown, if steady moisture, but not wetness, is

maintained.”

Origin of the Name.—Mr. Roe again : “ If there

were as much doubt about a crop of this fruit

as concerning the origin of its name, the out

look would be dismal indeed. In old Saxon, the

word was streawberige, or streowberrie; and was

so named, says one authority, ‘from the straw-

like stems of the plant, or from the berries lying

strewn upon the ground.’ Another authority

tells us : ‘It is an old English practice’ (let us

hope a modern one also) ‘to lay straw between

the rows to preserve the fruit from rotting on

the wet ground, from which the name has been

supposed to be derived ; although more probably

it is from the wandering habit of the plant, straw

being a corruption of the Anglo-Saxon strœ,

from which we have the English verb stray.’

Again, tradition asserts that in the olden times

children strung the berries on straws for sale,

and hence the name. Several other causes have

been suggested, but I forbear. I have never

known, however, a person to decline the fruit on

the ground of this obscurity and doubt.” John-

son‘s Cyclopedia less poetically reads, “and re

quire in winter a covering of straw, whence the

name.”

RASPBERRIES.

What the Raspberry is.—Rubus Idœus, the most

valued of all the species Rubus. It has pinnate

leaves, with five or three leaflets, which are white

and very downy beneath; stems nearly erect,

downy, and covered with very numerous small

weak prickles ; drooping flowers, and erect whit

ish petals as long as the calyx. The wild rasp

berry has scarlet fruit. It is a low deciduous

shrub, originating from the Mount Ida bramble,

which appears to have reached the gardens of

Southern Europe from Mount Ida. “ It has a

perennial root, producing biennial woody stems

that reach a height of from three to six feet.

The stems do not usually bear until the second

year, and only that year, and are replaced by

new growth from the root. The flowers are

white or red, very unobtrusive, and rich in sweet

ness. Bees forsake all other flowers while rasp

berry blossoms last.

Native Red Species.—Prof. Gray thus describes

this species : “ R. Strigosus, Wild Red R. Com

mon, especially North; from two to three feet

high; the upright stems, stalks, etc., beset with

copious bristles, and some of them becoming

weak prickles, also glandular; leaflets oblong-

ovate, pointed, cut-serrate, white downy be

neath, the lateral ones (either one or two pairs)

not stalked ; petals as long as the sepals ; fruit

light red, tender and watery, but high-flavored,

ripening all summer.”

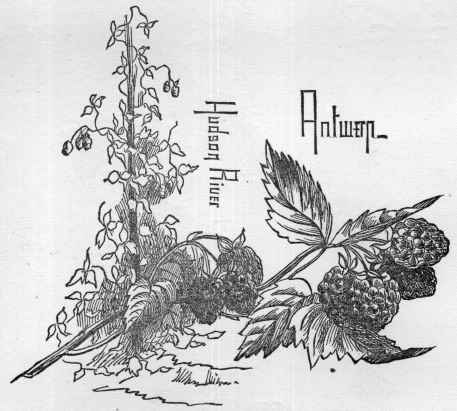

Red Antwerp of England.—This is the best known

of the imported varieties. Canes strong and tall.

Spines light red, rather numerous and pretty

strong. Fruit large, nearly globular or obtuse-

conical. Color dark red, with large grains, and

covered with a thick bloom. Flesh juicy, with

a brisk vinous flavor. Few old-fashioned gar

dens were without this berry, but it is giving

BERRIES. ‘ 119

way to newer and more popular varieties. The

fruit is too soft for market, but makes a dainty

dish for home use for those who still cultivate it.

The Hudson River Antwerp is the most cultivated

foreign berry in America, quite distinct from the

above, though belonging to the same family. Its

firmness of flesh, and parting readily from the

germ, together with its productiveness, render it

the most popular variety for market. Canes

short, but of sturdy growth, almost spineless,’ of

a very peculiar gray or mouse-color. Fruit

large, conical. Flesh firm, rather dull red, with

a slight bloom, not very juicy, but of a pleasant,

sweet flavor. Said to have been brought to this

country by the late Mr. Briggs, of Poughkeepsie,

N. Y., to whom it was given by a friend, since he

was leaving the country and could not interfere

with its sale in Europe. The owner had refused

three guineas for a single plant. But the variety

for some hidden reason has not flourished except

in a small area on the Hudson River, in Milton

and a little north and south of it. And now a

disease called the “ curl-leaf " threatens its extinc

tion even there. In its prime the line of wagons

at Marlboro landing was often nearly a mile long,

and it is estimated that in a single season

1,ooo,ooo pint baskets, about 14,700 bushels, were

shipped from that landing. But now, Ichabod !

its glory has departed.

The Fastollf is an English variety of high repu

tation. It derives its name from having origina

ted near the ruins of an old castle, so called, in

Great Yarmouth. Canes strong, rather erect,

branching, light yellowish brown, with few pretty

strong bristles. Fruit very large, obtuse or round

ish conical, bright purplish red, rich and high-

flavored, slightly adhering to the germ in pick

ing.

Knevet‘s Giant.—This is one of the strongest

growing varieties, very productive, and of excel

lent flavor. Canes strong, erect. Spines small,

reddish, very few. Fruit of the largest size, ob

tuse-conical, deep red, firm in texture, and hangs

a little to the germ in picking. Berries some

times double, giving them a coxcomb appear

ance.

The Franconia is now the best foreign variety

we have. It was introduced from Paris, more

than thirty years ago. Its crops are abundant,

the fruit is firm, and bears carriage to market

well, and ripens about a week later than Red

Antwerp. It is one of the finest for preserving.

Canes strong, spreading, branching, yellowish

brown, with scattered, rather stout purple spines.

Leaves rather large, very deep green. Fruit

large, obtuse-conical, dark purplish red, of a rich

acid flavor, much more tart and brisk than that

of the Red Antwerp. Its long continuance in

120 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

BERRIES. 121

bearing is one of its best qualities, as it lasts six

weeks. It is hardy, and well adapted to high

latitudes.

Belle de Fontenay.—This variety produces its

fruit mainly in the autumn. Suckers freely, and

requires to be carefully thinned out. The canes

should all be cut down in the spring in order to

obtain good crops. Canes strong, stout, branch

ing. Spines purplish, short and stiff, quite nu

merous. Fruit large, long, conical. Grains

large, dark crimson, thin bloom. Flesh moder

ately firm, juicy, sprightly; adheres slightly to

the core. It is said to be entirely hardy, and

to survive the winter without protection a hun

dred miles north of New York. Roe says: “ Its

most marked characteristic is a second crop in

autumn, produced on the tips of the new canes.

If the canes of the previous year are cut even with

the ground early in spring, the new growth gives

a very abundant autumn crop of berries, which,

although much inclined to crumble in picking,

have still the rare flavor of a delicious fruit long

out of season. It certainly is the best of the fall-

bearing kinds, and deserves a place in every gar

den. There are more profitable market varieties,

however; but if the suckers are vigorously de

stroyed, and the bearing canes cut well back, the

fruit is often very large, abundant and attractive,

bringing the highest prices.”

But the R. Strigosus, our native species, is

scattered almost everywhere throughout the

North, growing wild by hedges and walls, in

forest-glades and in the open fields. Especially

where land has been cleared up and left does this

berry spring up and cover acres and miles. Oc

casionally a bush is found whose fine fruit causes

its transfer to a garden, and a new variety is thus

introduced.

The Turner.—This is a hardy variety origina

ting in the garden of Prof. J. B. Turner, Jack

sonville, Fla.; it appears to succeed in more lo

calities than any of the red varieties, and is less

subject to changes in temperature; the canes,

foliage and fruit possess many characteristics of

the native red berry, and it suckers quite as

freely; canes vigorous, light reddish on the

sunny side; upright, seldom with branches; very

few short, purplish spines; foliage quite large

and abundant; very productive. Fruit medium

or above, roundish conical, bright scarlet; grains

of medium size, compact; flesh rather soft, sweet,

pleasant, but not rich. A good berry for home

use, but not quite firm enough for a distant mar

ket. Roe regards it as the hardiest raspberry in

122 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

cultivation, and says that a winter must be se

vere indeed that injures it.

The Brandywine.—This berry has been widely

popular, its origin being unknown. It became

the principal raspberry grown along the Brandy-

wine Creek, and took among the marketmen the

name of its chief haunt, which it still bears.

Its bright color, good size and its firmness and

great carrying qualities lead to its ready sale, but

its dry texture and insipid flavor are against it,

and it is giving place to

The Cuthbert—This is a chance seedling, ori

ginating in the garden of the late Thomas Cuth-

bert, of Riverdale, N. Y. Quite hardy; a valua

ble market variety, and one of the best for family

use ; very productive ; canes strong, vigorous, up

right, sometimes branching; spines short, stout,

purplish, rather numerous ; suckers freely, rather

too much so. Fruit medium to large, scarlet-

crimson, roundish, obtuse-conical; grains rather

small, compact, separate freely from the stalk ;

flesh quite firm, juicy, sweet, sprightly, having a

slight flavor of the common Red, which is pro

bably one of its parents.

Black-Caps.—This family is now numerous, of

large size and good quality. Prominent are the

Gregg, the Mammoth Cluster, Sweet Home, Sur

prise, Elsie, Davidson s Thornless, Doolittle, etc.

The Gregg was found in 1866 growing wild in a

ravine on the Gregg farm, Ohio Co., Ia. Its

owners claim that it survives the coldest winters,

and has never failed to produce an abundant

crop. It is a vigorous, rapid grower, producing

strong, well-matured canes by fall. The fruit is

beautiful in appearance, and delicious, possessing

excellent shipping and keeping qualities.

Soil and Culture.—The soil should be a rich deep

loam, rather moist than dry. Plant the suckers

or canes in rows from three to four feet apart,

according to the vigor of the sort. Two or three

suckers are generally planted together to form a

group or stool, and these stools may be three feet

apart in the rows, or they may be set one plant

in a place, a foot or 18 inches apart in the

row. The plantation being made should re

ceive a pruning every year, early in the spring.

Examine the stools in April, and, leaving three

or five of the strongest shoots or suckers to each

stool, cut away the old wood and the other

suckers. Cut off about a foot of the ends of

the remaining shoots. After the fruit is gathered

cut out the old canes which have fruited, and

give the new a better chance to ripen. Top-dress

lightly with manure, and keep down, or better

still keep out, the weeds.

Propagation.—The raspberry is usually propa

gated by suckers, springing up from the main

roots. It may be grown also from pieces of

roots, an inch or two long, planted in a light

sandy soil in early spring, covering an inch deep,

and adding a slight coat of light mulch.

Manures.—The stronger growing raspberries,

like the Cuthbert and the Turner, must not be

over-fertilized. But generally they thrive on

such manuring as is adapted for strawberries.

Muck, sweetened by lime and frost, is capital,

but any manure can be well used that is not too

full of heat and ferment. The raspberry needs

cool manures with staying qualities. Bone-dust,

ashes, poudrette and barnyard manure can be

alternated with the muck and lime, and a planta

tion thus treated kept in bearing nearly or quite

2o years.

BLACKBERRIES.

What they are.—Professor Gray thus describes

the two leading species of this bramble:

“ Rubus Villosus, High Blackberry. Every

where along thickets, fence-rows, etc., and seve

ral varieties cultivated ; stems one to six feet

high, furrowed; prickles strong and hooked;

leaflets three to five, ovate or lance ovate,

pointed, their lower surface and stalks hairy

and glandular, the middle one long-stalked and

sometimes heart-shaped ; flowers racemed, rather

large, with short bracts; fruit oblong or cylin

drical.

“ R. Canadensis, Low Blackberry or Dewberry.

Rocky and sandy soil; long-trailing, slightly

prickly, smooth or smoothish, and with three

to seven smaller leaflets than in the foregoing,

the racemes of flowers with more leaf-like bracts,

the fruit of fewer grains and ripening earlier.”

Downing says: The fruit is larger than that

of the Raspberry, with fewer and larger grains,

and a brisker flavor. It ripens about the last of

July or early in August, after the former is past,

and is much used by all classes in this country.

There is no doubt that varieties of much larger

size, and greatly superior flavor, might be pro

duced by sowing the seeds in rich garden soil,

especially if repeated for two or three successive

generations. Their cultivation in gardens is

similar to that of the raspberry, except that

they require to be planted at greater distances

apart, say from six to eight feet.

The Lawton or New Rochelle.—The first great step

away from the original bramble, the wild black

berry, was taken years ago by Mr. L. A. Secor,

who civilized a bush he found growing by the

roadside in New Rochelle, N. Y. This variety

took kindly to the garden, and has done more

to introduce the fruit than all other kinds to

gether. It is of very vigorous growth, with strong

spines, is hardy and exceedingly productive.

Fruit very large, oval, and, when fully ripe, in

tensely black. When ripe the fruit is very juicy,

rather soft and tender, with a sweet, excellent

BERRIES. 123

flavor; when gathered too early, it is acid and

insipid. The granules are larger, consequently

the fruit is less seedy than any other variety.

Ripens about the first of August, and continues

five or six weeks. “ Ik Marvel “ talks of it:

“ The New Rochelle or Lawton blackberry has

been despitefully spoken of by many; first, be

cause the market fruit is generally bad, being

plucked before it is fully ripened; and next, be

cause in rich, clayey grounds, the briers, unless

severely cut back, grow into a tangled, unap

proachable forest, with all the juices exhausted

in wood. But upon a soil moderately rich, a

little gravelly and warm, protected from winds,

served with occasional top-dressing and good

hoeing, the Lawton bears magnificent burdens.

Even then, if you wish to enjoy the richness of

the fruit, you must not be hasty to pluck it.

When the children say, with a shout, ‘ The black

berries are ripe! ’ I know they are black only, and

I can wait. When the children report, ‘The

birds are eating the berries! ’ I know I can wait.

But when they say, ‘ The bees are on the ber

ries V I know they are at their ripest. Then,

with baskets, we sally out; I taking the middle

rank, and the children the outer spray of boughs.

Even now we gather those only which drop at

the touch; these, in a brimming saucer, with

golden Alderney cream and a soupçon of pow

dered sugar, are Olympian nectar; they melt be

fore the tongue can measure their full round

ness, and seem to be mere bloated bubbles of

forest honev. "

The Kittatinnv Blackberry.

The Kittatinny.— Despite Mr. Mitchell‘s elo

quence the Lawton is giving way to new and

better-liked varieties, prominent among which

is the Kittatinny. This is a native wildling in

troduced by Mr. Wolverton, who found it grow

ing in a forest near the Kittatinny Mountains,

Warren Co., N. J. It has become widely dis

seminated, and everywhere proves of the highest

value. Canes quite hardy, and very productive;

ripening early, and continuing a long time. Fruit

large to very large, roundish, conical, rich glossy

black, moderately firm, juicy, rich, sweet, ex

cellent. Roe says that Mr. Wolverton, in find

ing it, has done more for the world than if he

had discovered a gold-mine. Both this and the

Lawton belong to the R. Villosus species.

Wilson’s Early.—This belongs to the other spe

cies, the R. Canadensis. Introduced by John

Wilson, Burlington, N. J. A hardy, productive,

very early ripening sort. Fruit large, oblong

oval, black. Flesh firm, sweet, good. The fruit

is earlier than the Kittatinny, and tends to ripen

altogether in about ten days. Its flavor is infe

rior to that of the Kittatinny or Snyder, and it

is too tender for the North and West.

The Snyder.—This belongs to R. Villosus, ori

ginating near La Porte, Ia, about 1851, and is an

upright, exceedingly vigorous and stocky grower.

It is too small to compete with the already

described berries, yet Mr. Roe thinks “that on

moist land, with judicious pruning, it could be

made to approach them very nearly, however,

while its earliness, hardiness, fine flavor, and

124 ‘ THE FRIEND OF ALL.

BERRIES. 125

ability to grow and yield abundantly almost any

where, will lead to an increasing popularity.

For home use, size is not so important as flavor

and the certainty of a crop. It is also more

nearly ripe when first black than any other kind

that I have seen ; its thorns are straight, and

therefore less vicious. I find that it is growing

steadily in favor; and where the Kittatinny is

winterkilled, this hardy new variety leaves little

cause for repining.”

Soil and Culture.—The blackberry does best on

light soils and in sunny exposures. The moist,

heavy, partially shaded land which is best for

the raspberry will send the growth of the black

berry into canes. The land should be warm

and well-drained, but not dry: as on hard dry

ground the fruit is liable not to mature, but

to become mere collections of seeds. Deep

plowing, and if possible following with the

lifting-plow to loosen the subsoil, as the roots

Red Dutch Currant.

require a large spread. Bushes should not be

allowed to grow over four feet high, and when

there is danger of winterkilling three feet is

enough, that the snow may cover and protect

them.

CURRANTS.

Professor Gray thus describes

“ Ribes Rubrum, Red Currant, cultivated from

Europe, also wild on our Northern border, with

straggling or reclining stems, somewhat heart-

shaped, three-to five-lobed leaves, the lobes

roundish and drooping racemes from lateral buds

distinct from the leaf-buds; edible berries red,

or a white variety.” The name is conjectured

to be a modification of Corinth, which once ex

ported so exclusively the small Zante grape.

Origin of our Cultivated Varieties. — These all

sprang from the imported varieties mentioned

above, or have been developed from wild speci-

126 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

mens found in the woods. Patience and perse

verance working with nature, have done won

ders.

Red Dutch.—This is an old, well-known sort,

thrifty, upright growth, very productive. Fruit

large, deep red, rich acid flavor, with clusters

two or three inches long. Of this Mr. Roe says :

“ It is the currant of memory. From it was

made the wine which our mothers and grand

mothers felt that they could offer with perfect

propriety to the minister. There are rural

homes today in which the impression still lin

gers that it is a kind of temperance drink.

From it is usually made the currant-jelly, with

out which no lady would think of keeping house

in the country. In flavor the Red Dutch is un-

equaled by any other red currant. It is also a

variety that can scarcely be killed by abuse and

Neglect, and it responds so generously to high

culture and vigorous pruning, that it is an open

question whether it cannot be made, after all,

the most profitable for market, since it is so

much more productive than the larger varieties,

and can be made to approach them so nearly in

size. Indeed, not a few are annually sold for

Cherry-currants.”

The White Dutch.—This is precisely similar to

the Red Dutch in habit, but the fruit is larger,

with rather shorter bunches, of a fine yellowish-

white color, with a very transparent skin. It is

considerably less acid than the red, and is there

fore much preferred for the table. It is also a

few days earlier. Very productive.

White Grape.—An advance in size of the White

Dutch. Bunches moderately long. berries very

large, whitish yellow, sweet and good. Very

productive. Branches more horizontal than

White Dutch, and less vigorous.

The Cherry-Currant.—This is the great market

currant. A strong-growing variety, with stout

erect, short jointed shoots. Leaves large, thick

and dark green. Not any more productive than

other currants, but a valuable one for market or

account of its size. Fruit of the very largest

BERRIES.

127

size. Bunches short. Berries deep red, and I

rather more acid than Red Dutch. The Cana

dian Horticulturist, September 1878, reads: “ The

history of this handsome currant is not without

interest. Mons. Adrienne Seneclause, a distin

guished horticulturist in France, received it from

Italy among a lot of other currants. He noticed

the extraordinary size of the fruit, and gave it, \

in consequence, the name it yet bears. In the

year 1843, it was fruited in the nursery of the

Museum of Natural History, and figured from

these samples in the Annales de Flore et de Po-

mone for February, 1848. Dr. William W. Valk,

of Flushing, Long Island, N. Y., introduced it to

the notice of American fruit-growers in 1846,

having imported some of the plants in the spring

of that year.”

The Versailles, La Versaillaise, so nearly resem

bles the cherry-currant, that the opinion is quite

general that the two are nearly or quite identical.

Mr. Downing finds a difference in the fact that

while the Versailles strain produces many short

bunches like the Cherry, it also frequently bears

long tapering clusters such as are never formed

on the Cherry. Mr. Roe has not been able to

verify even this distinction.

The Victoria, often called May’s Victoria, is a

very excellent, rather late sort, with very long

bunches of bright red fruit, and is an acquisition

to this class. Berries as large as Red Dutch.

Bunches rather longer, of a brighter red, growth

more slow, spreading, and very productive.

Will hang on the bushes some two weeks longer

than most currants.

Black Currants form a distinct class, not nearly

as popular here as in England. They are stronger

and coarser growing plants than the red and

white species, and do not demand as high culture.

There are several varieties grown here, but on a

limited scale: the. Bang Up, the Black Grape, the

Black Naples, the English Black, the Common

Black and Lees Prolific.

Choice and Preparation of Soil.—Mr. Roe says ;

“ The secret of success in the culture of currants

is suggested by the fact that nature has planted

nearly every species of the Ribes in cold, damp,

northern exposures. Throughout the woods

and bogs of the Northern Hemisphere is found

the scraggy, untamed, hardy stock from which

has been developed the superb White Grape.

Development does not eradicate constitutional

traits and tendencies. Beneath all is the craving

for primeval conditions of life, and the best success

with the currant and gooseberry will assuredly be

obtained by those who can give them a reasonable

approach to the soil, climate and culture suggested

by their damp, cold native haunts. The first requi

site is not wetness, but abundant and continuous

moisture. Soils naturally deficient in this, and

which cannot be made drought-resisting by deep

plowing and cultivation, are not adapted to the

currant. . . . Damp, heavy land, that is capable of

deep, thorough cultivation, should be selected if

possible. When such is not to be had, then, by

deep plowing, subsoiling, by abundant mulch

around the plants throughout the summer, and by

occasional waterings in the garden, counteracting

the effects of lightness and dryness of soil, skill

can go far in making good nature’s deficiencies.

“ Next to depth of soil and moisture, the cur

rant requires fertility. It is justly called one of

the ‘ gross feeders,’ and is not particular as to

the quality of its food, so that it is abundant. I

would still suggest, however, that it be fed ac

cording to its nature, with heavy composts, in

which muck, leaf-mold, and the cleanings of the

cow-stable, are largely present. Wood-ashes and

bone-meal are also most excellent.”

Planting.—Autumn is the best season for plant

ing currants, and early spring nearly as good.

There is little danger of the plants dying at any

time if kept moist. The young bushes should

be cut back after planting, half or two thirds.

If rows are five feet apart, and the plants fout

feet apart in the rows, an acre will hold 2178

plants. If set at right angles five feet apart, an

acre will hold 1742 plants. They ought to be

set about three inches deeper than they stood in

the nursery, and should have a shovel-full of com

post around each young plant. Mr. Roe recom

mends the bush and not the tree form when cur

rants are to be grown for market.

GOOSEBERRIES.

Description.—The gooseberry (Grossularid) is a

sub-genus of the genus Ribes, to which the currant

belongs, distinguished by a thorny stem, a more or

less bell-shaped calyx, and flowers on one-to-three

flowered stalks. The common gooseberry is a

native of many parts of Europe and northern

Asia, growing wild in rocky situations and in

thickets, particularly in mountainous districts.

The varieties produced by cultivation in England

are very numerous, where, and especially in Lan

caster, greater attention is paid to its cultivation

than in any other part of the world. The Lan

caster annual shows exhibit this fruit in its great

est perfection, and a Gooseberry Book is published

annually at Manchester, giving a list of prize

sorts, etc. More than a hundred and fifty exhi

bitions have been made in a single year, and the

berry, which in its wild state weighs only about

I one quarter of an ounce, and is a half-inch in

diameter, has been cultivated to a size of two

inches in diameter and the weight of an ounce

and a half. But the English climate, with its

moisture and coolness, seems especially fitted for

I the growth of this fruit, and under our clear and

128 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

hot suns the best varieties of English sorts do

not thrive, mildew of fruit and foliage being their

steady enemy. But on the other side, as Mr.

Downing writes, “ we are indebted to the Lan

cashire weavers, who seem to have taken it up

as a hobby, for nearly all the surprisingly large

sorts of modern date.”

Foreign Varieties.—As these cannot be depended

upon to flourish here, it will be enough merely to

give the names of a few leading varieties:—Red

Gooseberries: Boardman’s British Crown,

Champagne, Melting’s Crown Bob; Yellow

Gooseberries: Buerdsill’s Duckwing, Hill’s

Golden Gourd, Yellow Ball; Green Goose

berries: Colliers Jolly Angler, Green Walnut,

Wainman’s Green Ocean; White GOOSE

BERRIES: Crompton’s Sheba Queen, Saunders’

Cheshire Lass, Taylor‘s Bright Venus. (These

names, and many others, suggest the yearning of

the weavers to find the ideal in the actual.)

Seedlings of these foreign varieties have the

same tendency to mildew shown by their parents.

The Ribes Hirtellum is described by Prof. Gray

as the “ commonest in our Eastern States, seldom

downy, with very short thorns or none, very short

peduncles, stamens and two-cleft style scarcely

longer than the bell-shaped calyx; and the

smooth berry is purple, small and sweet.” This is

the parent of the most widely known of our native

varieties, first among which may be mentioned

The Houghton Seedling.—This originated with

Abel Houghton, Lynn, Mass. A vigorous grow

er ; branches rather drooping, slender, very pro-

Houghton’s Seedling.

ductive, generally free from mildew; a desirable

sort. Fruit medium or below, roundish, inclin

ing to oval. Skin smooth, pale red. Flesh ten

der, sweet and very good. It improves greatly

under high culture and pruning.

The bush has a slender and even weeping

habit of growth, and can be propagated readily

by cuttings.

Downing.—This is a seedling of the Houghtom

originated by Mr. Charles Downing, of New-

burgh, N. Y. An upright, vigorous growing

plant, very productive. Fruit somewhat larger

than the Houghton, roundish oval, whitish green,

with the rib-veins distinct. Skin smooth. Flesh

rather soft, juicy, very good. Excellent for

family use. Mr. Roe says : “ I consider this the

best and most profitable variety that can be gen

erally grown in this country. In flavor it is ex

cellent. I have had good success with it when

ever I have given it fair culture. It does not

propagate readily from cuttings, and therefore I

increase it usually by layering.”

Smith’s Improved.—A new variety grown from

the seed of the Houghton by Dr. Smith, of Ver

mont, and in growth of plant more upright and

vigorous than its parent; the fruit is larger, and

somewhat oval in form, light green, with a

bloom. Flesh moderately firm, sweet and good.

Hobbs’ Seedling.—A variety said to have been

originated by O. J. Hobbs, of Randolph, Pa.

Light pale green, roundish, slightly oval, smooth.

Flesh medium firmness. A good keeper, and

nearly one half larger than Houghton‘s.

• BERRIES. 129

Mountain Seedling.—Originated with the Shakers

at Lebanon, N. Y. Plant a strong, straggling

grower, and an abundant bearer. Fruit large, the

largest of any known American sort, long oval,

dark brownish red, with long stalk. Skin smooth,

thick. Flesh sweet. A good market sort.

Pale Red.—A variety of unknown origin. Bush

more upright than Houghton. Slender wood.

Very productive. Fruit small or medium, about

the size of the Houghton ; darker in color when

fully ripe. Hangs a long time upon the bush.

Flesh tender, sweet, very good.

Chester, or American Red, is an old variety, whose

origin is unknown—probably its ancestors grew

wild in the woods. Fruit not quite as large as

the Houghton, when fully ripe darker than that,

hangs long on the bush, and is sweet and good.

Said not to mildew. Such characteristics point

it out as suitable for a parent of new varieties.

Cultivation.—Like its near relative the currant,

it flourishes best in cool exposures, and is the

better for partial shade. A rich soil, especially

one deep and moist, is equally requisite, and

vigorous annual pruning is essential. It is im

patient of drought, and needs a deep, strong

loam. Don‘t put it under other trees for the

sake of shade, as that deteriorates the fruit in

9

flavor and size, and, its vitality thus reduced, it

is more liable to mold. The plants should only

be raised from cuttings, unless the object be to

produce a new variety, which of course must be

raised from seed. The Encyclopœdia of Garden

ing thus describes the pains taken by Lancashire

cultivators : “ To effect this increased size, every

stimulant is applied that their ingenuity can sug

gest. They not only annually manure the soil

richly, but also surround the plants with trenches

of manure for the extremities of the roots to

strike into, and form around the stem of each

plant a basin, to be mulched, or manured, or

watered, as may become necessary, Whea a

root has extended too far from the stem, it is

uncovered, and all the strongest leaders are

shortened back nearly one half of their length,

and covered with fresh, marly loam, well ma

nured. The effect of this pruning is to increase

the number of fibers and spongioles, which form

rapidly on the shortened roots, and strike out in

all directions among the fresh, newly stirred

loam, in search of nutriment.”

In large plantations, and where cultivation is

given by means of the horse and plow, the sys

tem of growing in the bush form is by many

considered most profitable.

130

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

CRANBERRIES.

Description.—Downing says : This is a familiar

trailing shrub, growing wild in swampy, sandy

meadows, and mossy bogs, and produces a round

red, acid fruit. Our native species Oxycoccus

Macrocarpus, so common in the swamps of New

England, and on the borders of our inland lakes,

as to form quite an article of commerce, is much

the largest and finest species; the European

cranberry being much smaller in its growth, and

producing inferior fruit.

If Downing‘s description is not formal enough,

take this from the Encyclopaedia Britannica:

" O. palustris, the common cranberry plant, is

found in marshy land in northern and central

Europe and North America. Its stems are wiry,

creeping, and of varying length ; the leaves are

evergreen, dark and shining above, glaucous be

low, revolute at the margin, ovate, lanceolate or

elliptical in shape, and not more than half an inch

long; the flowers, which appear in May or June,

are small and pedunculate, and have a four-lobed,

rose-tinted corolla, purplish filaments, and an

ther-cell, forming two long tubes; the berries

ripen in August and September; they are pear-

shaped, and about the size of currants, are crim

son in color, and often spotted, and have an acid

and astringent taste.”

Of the 0. Macrocarpus, there are three varie

ties: the Bell-Shaped, which is the largest and

most valued, of a very dark, bright red color.

The Cherry, two kinds, large and small; the large

one the best, of a round form, a fine dark red berry,

nearly or quite equal to the Bell-shaped ; and the

Bugle, Oval, or Egg-Shaped, two kinds, large and

small, not so high-colored as the Bell and Cher

ry—not so much prized, but still a fine variety.

Cultivation.—Although, naturally, it grows most

ly in mossy, wet land, yet it may be easily culti

vated in beds of peat soil, made in any rather

moist situation ; and if a third of old thoroughly

decayed manure is added to the peat, the berries

will be much larger, and of more agreeable flavor

than the wild ones. A square of the size of

twenty feet, planted in this way, will yield three

or four bushels annually. The plants are easily

procured, and are generally taken up like squares

of sod or turf, and planted two or three feet

apart, when they quickly cover the whole beds.

Cape Cod Culture.—The Cranberry grows freely

in light soils, but the surface should be covered,

after plowing, with clean sand a depth of several

inches. Eighty to a hundred bushels to the acre

is an average product, and the care they require

after the land is once prepared and planted, is

next to nothing till they are ready to gather.

Some farms in Massachusetts bear large crops,

partly natural, partly cultivated. The berry grows

wild in the greatest abundance on the sandy low

necks near Barnstable, and an annual festival is

made of the gathering of the fruit, which is done

by the mass of the residents, who turn out on a

day appointed by the authorities, and make a

general gathering with their cranberry rakes, a

certain portion of the crop belonging and deliv

ered to the town. One man with his rake will

gather about thirty bushels a day. The rake,

however, is wasteful; and where cranberries are

grown on private property, and picked by hand,

three bushels is somewhere near the average

picking of a day.

Results.—Joseph J. White, in Cranberry Cul

ture, tells of a “ little pond “ in Burlington Co.,

N. J., containing twelve acres. After being

planted ten years at an original cost of not ex

ceeding $500, he saw a patch of vigorous vines,

from which the proprietor told him he never

gathered at one picking less than a bushel and

a half per square rod, and sometimes they

yielded two bushels. A square rod of the best

vines was staked off, and the berries carefully

picked. The yield was six bushels and two

quarts, or at the rate of 970 bushels to the acre.

Three acres of this meadow netted $1800 in one

year. Of course, this is an extreme case.

The Name is supposed to have been derived

from the appearance of the bud. Just before

expanding into the perfect flower, the stem,

calyx and petals resemble the neck, head and

bill of a crane ; and so cranberry may be a short

ening of craneberry.

Uses.—In addition to their value in the differ

ent forms of Cranberry Sauce, Cranberry Pie,

Preserved and Canned Cranberries, and the well-

known accompaniment to fowls, they are com

ing into use on shipboard as an antiscorbutic,

and in Europe a wine is made from them. White

tells of an Englishman, who receiving a barrel

of cranberries from a friend in America, ac

knowledged their receipt, stating that “the ber

ries arrived safely, but they soured on the pas

sage” leaving his American friend to infer that

I the uncooked fruit was served up in cream.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |