HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT.

131

IN AND ABOUT THE BARN.

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT.

After Fasting........................ 136

Air, Circulation of................... 133

Bread for the Stable................. 137

Breeding and Training:

Abortion........................... 138

Bearing-Rein, the.................. 142

" Breaking” Horses................ 140

Breed for what you want........... 137

Breeding in-and-in................. 138

Check-Rein, the.................... 142

Colt, Training the.................. 140

Directions, Rarey’s................ 139

Exercise........................... 138

Foaling............................ 138

Foaling Time, Indications of....... 138

In-and-in Breeding................ 138

Indications of Foaling Time....... 138

Mare and Colt, the................. 138

Not too Early...................... 137

Proper Time, the.................. 138

Rarey’s Directions................. 139

Rein, the Check- .................. 142

Slinking the Foal.................. 138

Training the Colt.................. 140

Young Colt, the................... 139

Circulation of Air.................... 133

Corn, Indian......................... 136

Diseases and Accidents, and their

Treatment:

Abdomen, Dropsy of the........... 165

Abdominal Injuries................ 164

Abraded Wounds.................. 192

Abscess of the Brain............... 164

Acites.............................. 165

Acute Dysentery................... 165

Acute Gastritis..................... 165

Acute Laminitis.................... 165

Albuminous Urine................. 166

Angles of the Mouth, Excoriated .. 173

Aphtha............................ 166

Back Sinews, Clap of the........... 170

Back Sinews, Sprain of the......... 188

Biting, Crib....................... 172

Bladder, Inflammation of the...... 172

Bloody Urine...................... 176

Bog Spavin........................ 166

Bots............................... 166

Brain, Abscess of the.............. 164

Brain, Inflammation of the......... 166

Breaking Down.................... 166

Broken Knees...................... 167

Broken Wind...................... 167

Bronchitis.......................... 167

Bronchocele....................... 168

Bruise of the Sole.................. 168

Calculi............................. 168

Calculus........................... 164

Canker............................. 168

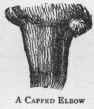

Capped Elbow..................... 169

Capped Hock...................... 169

Capped Knee...................... 169

Cartilages, Ossified................. 181

Gataract........................... 169

Diseases and Accidents:

Cavities, Open Synovial........... 181

Choking........................... 169

Chronic Dysentery................. 170

Chronic Gastritis................... 170

Chronic Hepatitis.................. 170

Clap of the Back Sinews........... 170

Cold............................... 171

Colic, Spasmodic................... 187

Colic, Windy...................... 191

Congestion in the Field............ 171

Congestion in the Stable........... 171

Contused Wounds.................. 192

Corns.............................. 171

Cough............................. 172

Cracked Heels...................... 172

Crib-Biting........................ 172

Curb............................... 172

Cystitis............................ 172

Diabetes........................... 173

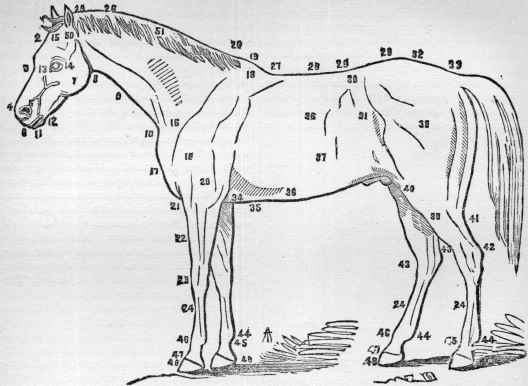

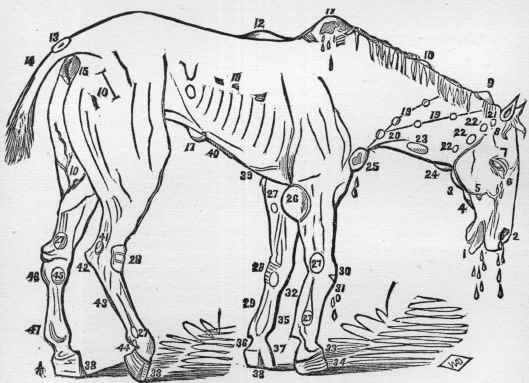

Diagram showing seat of diseases.. 163

Diaphragm, Spasm of.............. 187

Dropsy of the Abdomen........... 165

Dysentery, Acute.................. 165

Dysentery, Chronic................ 170

Elbow, Capped.................... 169

Enteritis........................... 173

Epizoöty.......................... 173

Excoriated Angles of the Mouth... 173

Eyes, Fungoid Tumor in the....... 174

Eyelid, Lacerated.................. 177

False Quarter...................... 173

Farcy.............................. 173

Farcy, Water...................... 191

Feet, Fever in the.................. 165

Fever in the Feet.................. 165

Field, Congestion in the........... 171

Fistulous Parotid Duct............. 174

Fistulous Withers.................. 174

Flexor Tendons, Strain of the...... 189

Foot, Pumice...................... 184

Fret.............................. 187

Fungoid Tumor in the Eyes....... 174

Gastritis, Acute.................... 165

Gastritis, Chronic.......,.......... 170

Glanders........................... 175

Gleet, Nasal....................... 179

Grease............................. 175

Gripes............................. 187

Gutta Serena....................... 175

Heart-Disease...................... 176

Heels, Cracked..................... 172

Hematuria......................... 176

Hemorrhagica, Purpura........... 184

Hepatitis, Chronic.................. 170

Hide-Bound....................... 176

High-Blowing...................... 176

Hock, Capped..................... 169

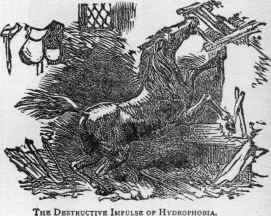

Hydrophobia...................... 176

Hydrothorax...................... 176

Impediment in Lachrymal Duct.... 177

Incised Wounds.................... 192

Inflammation of the Bladder....... 172

Diseases and Accidents:

Inflammation of the Brain......... 166

Inflammation of the Kidneys....... 180

Inflammation of the Vein.......... 182

Influenza........................... 177

Injuries, Abdominal................ 164

Injuries to the Jaw................. 177

Insipidus Diabetes................. 173

Introsusception.................... 164

Invagination....................... 164

Jaw, Injuries to the................ 177

Joints, Open Synovial.............. 181

Kidneys, Inflammation of the...... 180

Knees, Broken..................... 167

Knee, Capped...................... 169

Lacerated Eyelid.................. 177

Lacerated Tongue................. 177

Lacerated Wounds................. 192

Lachrymal Duct, Impediment in... 177

Laminitis, Acute.................. 165

Laminitis, Subacute................ 177

Laryngitis......................... 177

Larva in the Skin.................. 178

Legs, Swollen...................... 190

Lice............................... 178

Luxation of the Patella............ 178

Mallenders........................ 178

Mange............................. 178

Megrims........................... 179

Melanosis......................... 179

Mouth, Excoriated Angles of...... 173

Mouth, Scald...................... 186

Nasal Gleet....................... 179

Nasal Polypus..................... 179

Navicular Disease.................. 179

Nephritis.......................... 180

Occult Spavin..................... 180

Œsophagus, Stricture of........... 185

Open Synovial Cavities............ 181

Open Synovial Joints.............. 181

Ophthalmia, Simple................ 186

Ophthalmia, Specific............... 188

Ossified Cartilages................. 181

Overreach........................ 181

Paralysis, Partial.................. 182

Parotid Duct, Fistulous............ 174

Partial Paralysis................... 182

Patella, Luxation of the............ 178

Phlebitis........................... 182

Phrenitis................ .......... 182

Pleurisy............................ 182

Pneumonia......................... 183

Poll Evil........................... 183

Polypus, Nasal..................... 179

Prick of the Sole.................. 183

Profuse Staling.................... 173

Prurigo............................ 183

Pumice Foot....................... 184

Punctured Wounds................ 193

Purpura Hemorrhagica............ 184

Quarter, False..................... 173

Quittor............................ 184

Rheumatism....................... 184

132

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

Diseases and Accidents :

Ring-Bone......................... 185

Ringworm......................... 185

Roaring............................ 185

Rupture........................... 185

Ruptured Spleen................... 164

Ruptured Stomach................. 164

Sallenders......................... 178

Sand-Crack........................ 185

Scald Mouth....................... 186

Seedy Toe......................... 186

Simple Ophthalmia................ 186

Sinews, Sprain of the Back........ 188

Sitfast............................. 186

Skin, Larva in the................. 178

Sole, Bruise of the................. 168

Sole, Prick of the.................. 183

Sore Throat;....................... 186

Spasm of the Diaphragm.......... 187

Spasm of the Urethra.............. 187

Spasmodic Colic................... 187

Spavin............................. 187

Spavin, Bog....................... 166

Spavin, Occult..................... 180

Specific Ophthalmia................ 188

Spleen, Ruptured.................. 164

Splint.............................. 188

Sprain of the Back Sinews......... 188

Stable, Congestion in the........... 171

Staggers........................... 188

Staling, Profuse................... 173

Strain of the Flexor Tendons....... 189

Stomach, Ruptured................ 164

Strangles.......................... 189

Strangulation...................... 164

Stricture of the Œsophagus........ 185

Stringhalt.......................... 189

Surfeit............................. 189

Swollen Legs...................... 190

Synovial, Open Cavities............ 181

Synovial, Open Joints.............. 181

Teeth.............................. 190

Tendons, Flexor, Strain of......... 189

Tetanus............................ 190

Thorough-Pin..................... 190

Throat, Sore....................... 186

Thrush............................. 190

Toe, Seedy......................... 186

Tongue, Lacerated................ 177

Tread............................. 190

Tumors............................ 191

Tumors, Fungoid, in the Eye...... 174

Urine, Albuminous................ 166

Urine, Bloody...................... 176

Urethra, Spasm of................. 187

Vein, Inflammation of the...... ... 182

Warts............................ 191

Diseases and Accidents:

Water-Farcy....................... 191

Wheezing.......................... 176

Wind, Broken...................... 167

Wind-galls......................... 191

Windy Colic....................... 191

Withers, Fistulous................. 174

Worms............................. 192

Wounds............................ 192

Drainage............................ 134

Exercise............................. 135

Fasting, After....................... 136

Floors, and Paving.................. 133

Good Mashes........................ 137

Grooming............................ 134

Gruel for Horses..................... 136

Hay.................................. 135

Hay-Tea.............,............... 136

History, the Horse in................ 132

Horse in History, the................ 132

How to Feed........................ 136

Indian Corn.......................... 136

Light................................ 134

Litter................................ 134

Mashes, Good........................ 137

Oats................................. 135

Paving and Floors................... 133

Points:

Abdomen, the...................... 157

Back, the.......................... 154

Ear, the............................ 155

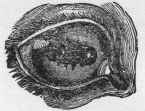

Eye, the........................... 156

Head, the.......................... 155

Lips, the........................... 156

Legs and Shoulders, the........... 158

Lower Leg, the.................... 158

Lumbar Region, the............... 153

Lungs and Thorax, the............ 158

Neck, the.......................... 155

Nostrils, the........................ 156

Shoulders and Legs, the............ 158

Stem and Rudder.................. 153

Tail, the........................... 154

Thorax and Lungs, the............ 157

Withers, the....................... 158

Remedies, and their Administration:

Aloes.............................. 194

Balling-Iron....................... 194

Ball passing down Gullet.......... 196

Balls............................... i94

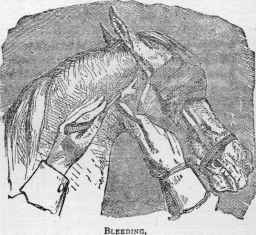

Bleeding........................... 199

Blisters............................ 198

Cut of Swallowing Ball............ 196

Cut of Bleeding a Horse........... 199

Cuts of Giving a Draught......... 198

Draughts, Giving.................. 197

Drinks............................. 196

Remedies, and their Administration:

Fleam, Open and Shut............. 199

Giving Draughts.................. 197

Holding the Pail..................200

Horse-Balls........................ 194

Horses not all Alike................ 193

Mashes, Warm..................... 193

New Balling Iron.................. 195

New Way of Giving Ball.......... 195

Old Way of Giving Ball........... 194

Other Physics...................... 194

Process of Drinking................ 196

Quiet Method of Giving Draught.. 198

Suture, Twisted.................... 200

Third Avenue Stables.............. 201

Tongue and Mouth................ 197

Turkish Bath....................... 200

Twisted Suture.................... 200

Warm Mashes..................... 193

Roots................................ 137

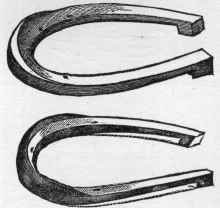

Shoeing:

Arab Method, the.................. 148

Boots.............................. 152

Calks.............................. 150

Cutting............................ 152

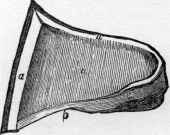

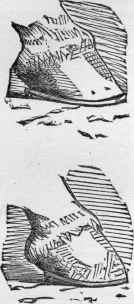

Hoof, Structure of................. 148

Interfering........................ 152

Method, the Arab.................. 148

Method, the Usual................. 148

Mischief from Separation.......... 148

Paring too Small........,.......... 151

Rarey‘s Directions................. 146

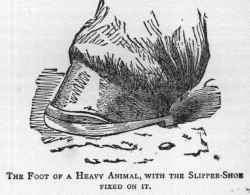

Shoe, the Slipper.................. 150

Slipper-Shoe, the.................. 150

Slippery Weather.................. 151

Structure of the Hoof.............. 148

Usual Method, the................. 148

Weather, Slippery................. 151

Sieve, Value of a..................... 137

Stable, the........................... 133

Stalls................................ 133

Straw................................ 137

Trash................................ 137

Teeth, the............................ 142

Value of a Sieve..................... 137

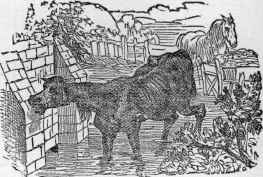

“ Vices,” so called :

Balking, or Jibbing................ 160

Chink in the Back................. 161

Horses not totally Depraved....... 160

Jibbing, or Balking................ 160

“ Kidney-Dropping”.............. 161

Rolling............................ 163

Shying and Swerving.............. 162

Tearing the Clothing.............. 162

“ Toothy” and “ Temper”......... 159

When to Feed........................ 136

Far back in History.—The origin of the horse

lies far back in antiquity, and his is a familiar

figure in almost all extant literature. Homer,

Hesiod and Pindar tell us not only of horses,

but of centaurs, half man and half horse, so that

long before their time the horse must have been

sufficiently conquered to the use of man to have

originated the old legend. The usual chronology

puts the Book of Job more than fifteen hundred

years before Christ; late investigators put it

nearly nine hundred years later. But the de

scription Jahweh gives Job of the horse indicates

that he must have been the same essentially

then as now: “ Hast thou given the horse

strength ? hast thou clothed his neck with thun

der? . . . the glory of his nostrils is terrible. . . .

He paweth in the valley, and rejoiceth in his

strength ; he goeth to meet the armed men,” etc.

The whole account is appropriate to the modern

war-horse; and it is quite doubtful whether the

naturalist, if he had the horse of Job‘s time,

Alexanders Bucephalus, and the charger Gen.

Sheridan rode to Winchester, could from any in

ternal indications determine which was which.

Undoubtedly if the best trotting-horses of each

age at intervals of five hundred years could be

speeded together, the date could be assigned to

each. When Hi. Woodruff drove at Fashion and

Union courses, the aim was a “ two-forty” gait;

now the flyers are hovering between " two-ten”

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT. 133

and “two-eleven,” and will soon be shading off

inside the ten. Such an animal as is now with

out any great difficulty to be had, deserves, and

will repay, careful and intelligent treatment.

The Stable.—This is a very important part of

the subject and one which is too often neglected

by people who own horses and who leave their

general management to stable-keepers or grooms

often grossly neglectful or ignorant. Many

horses die yearly from the neglect of their own

ers to enforce the ordinary laws of health in the

stable. A site should be chosen, nearly or quite

as well situated as that for the dwelling, and the

stable may be, if possible, separate and distinct

from the barn with advantage. Hide it if you

like behind trees, but do not cut off the

Circulation of Air.—A supply of pure air is as

necessary to the life and health of a horse as of

a man. In many stables air is carelessly ad

mitted and blows either on the head of the horse

or in such a way that cold and cough is the in

evitable result. The practice of feeding hay

through a hole above the head of the horse in

vites fatal results in the way of cold, not to men

tion the possibility of hayseed falling into the

eyes of the horse when it is looking up for its

food. An opposite error, however, is to exclude

every possible breath of air and have the atmos

phere of the stable hot and unwholesome. The

effect of several horses being shut up in one sta

ble is to render the air unpleasantly warm and

foul. A person coming from the open air can

not breathe it many minutes without perspiring.

In this temperature the horse stands, hour by

hour, often with a covering on; this is suddenly

stripped off, and it is led into the open air, the

temperature of which is many degrees below

that of the stable. It is true that while it is ex

ercising it has no need of protection ; but unfor

tunately it too often has to stand awaiting its

master’s convenience, and this perhaps after a

brisk trot which has opened every pore, and its

susceptibility to cold has been excited to the ut

most extent. In ventilating stables it should

never be forgotten that the health of a horse de

pends on an abundant supply of fresh dry air, in

troduced in such a manner as to prevent a pos

sible chance of a draught on any of its inmates.

Many old stables may be greatly benefited by

the introduction of a window or windows which

will require but little expenditure and save

many dollars worth of horseflesh.

Stalls.—Large stalls are to be preferred, and

each horse should have his separate stall. Each

stall should be ten feet from front to rear, and

with a width of five to five and a half feet. At

the foot of each stall should be a round partition

post set slightly inclining, so that the bottom

shall be ten feet and the top eight feet from the

head of the stall; the sides four and a half feet

high, of two-inch plank; and if unruly horses are

to be placed there, a couple of feet in height of

woven wire cloth should be added at the top.

Or, the stalls may be placed in rows each six

feet wide, nine feet long, with the height above

to the extent of fourteen feet. Three feet in

front of the manger gives room for the feed

to be brought and given, and six feet behind

the stalls gives space for proper cleaning.

If the size of the stable will admit of it, loose

boxes are of great benefit; and at all events there

should be one loose box for cases of sickness,

and this should be situated at some distance

from the other stalls, to prevent the spread of

any contagious disease.

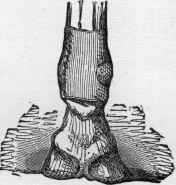

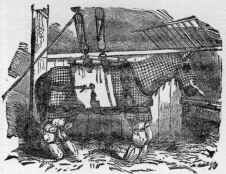

Floors, and their Paving.—One good plan is to

make the floor double, the upper one in three

parts; the first three feet in front, of two-inch

hardwood plank, should be laid close and nailed

solid; the other two sections of narrow hardwood

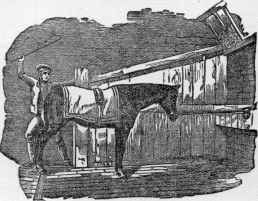

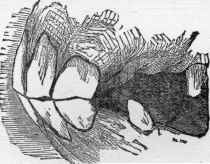

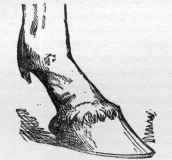

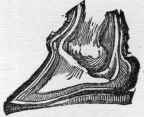

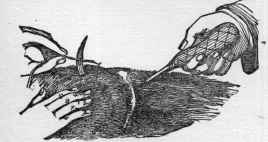

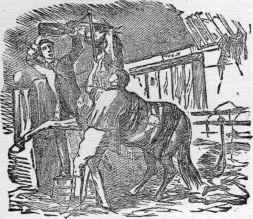

The Hind Feet are Eased in the Gutter.

plank, to be nailed on strong end-pieces, with half-

inch spaces between. These are to be hinged to

other plank nine inches wide, next the sides of the

stall, so as to shut together at the middle, to

within half an inch of each other. Thus, all the

liquid matter passes directly through to the solid

and water-tight floor beneath, made of planed

and grooved plank, and ending, just inside the

posts, in a narrow gutter, whence it may be con

veyed away to a tank.

Where there are irregularities, cleanliness is

almost impossible. A good material is stone

when well jointed. Cement, however, is the

best when properly laid, as its elasticity is a great

relief to the feet of a horse.

A slanting of the floor of the stalls should

never be allowed, as it is frequently the cause of

lameness and contraction of the heels. To keep

the feet on a level, horses will sometimes stand

out of their stalls with the hind feet over the

gutter, as in the cut above.

134 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

Drainage.—The stable snould be so contrived

that the urine shall quickly run off, and the of

fensive and injurious vapor from the decompos

ing urine and the litter will thus be materially

lessened : if, however, the urine be carried away

by means of a gutter running along the stable, it

must be so done as not to raise the level of the

horse’s hind feet above that of his forefeet. The

farmer should not lose any of the urine. It is

from the dung of the horse that he derives a

principal and the most valuable part of his ma

nure. It is that which earliest takes on the pro

cess of decomposition, and forms one of the

strongest and most durable dressings. That

which is most of all concerned with the rapidity

and perfection of the process is the urine.

Litter.—Some intelligent persons have com

plained much of the influence of litter. If the

horse stand many hours in the day with his foot

embedded in straw, it is supposed that the hoof

must be unnaturally heated ; and it is said that

the horn will contract under the influence of

heat. It is seldom, however, that the foot is so

surrounded by the litter that its heat will be

sufficiently increased to produce this effect on

the thick horn. The foot is not sufficiently long

or deeply covered by the litter to produce a tem

perature high enough to warp the hoof. We are

not the disciples of those who would, during the

day, remove all litter from under the horse; we

do not like the naked and uncomfortable appear

ance of the stable. Humanity and a proper care

of the foot of the horse should induce us to keep

some litter under him during the day; but his

feet need not sink so deeply in it that their tem

perature should be much affected.

Great care should be taken that every portion

of litter be removed that has been wet by urine,

as decay commences very quickly and the gases

given off in that state are highly injurious. In

some stables piles of litter are allowed to accu

mulate and serve as a cloak for great unclean-

liness; this should never be permitted.

Light.-This neglected branch of stable-manage

ment is of far more consequence than is generally

imagined. The stable is frequently destitute of

any glazed window; and has only a shutter,

which is raised in warm, and shut down in cold

weather. When the horse is in the stable only

during a few hours of the day, this is not of so

much consequence ; nor of so much, probably, to

horses of slow work ; but to carriage and road

horses, so far at least as the eyes are concerned, a

dark stable is little less injurious than a foul and

heated one. To illustrate this, reference may be

made to the unpleasant feeling and the utter im

possibility of seeing distinctly, when a man sud

denly emerges from a dark place into the full

blaze of day. The sensation of mingled pain and

giddiness is not soon forgotten; and some time

passes before the eye can accommodate itself to

the increased light. If this were to happen every

day, or several times in the day, the sight would

be irreparably injured; or, possibly, blindness

would ensue. Can we wonder, then, that the

horse taken from a dark stable into a glare of

light, and feeling, probably, as we should under

similar circumstances, and unable, for a consider

able time, to see anything around him distinctly,

should become a starter, or that the frequently

repeated violent effect of sudden light should in

duce inflammation of the eye, so intense as to

terminate in blindness? There is, indeed, no

doubt, in the mind of any one familiar with the

subject, that horses kept in a dark stable are fre

quently notorious starters, and that starting has

been evidently traced to this cause.

If plenty of light be admitted, the walls of the

stable, and especially that portion of them which

is before the horse’s head, must not be of too

glaring a color. The constant reflection from a

white wall, and especially if the sun shines into

the stable, will be as injurious to the eye as the

sudden changes from darkness to light. The

perpetual slight excess of stimulus will do as

much mischief as the occasional but more violent

one, when the animal is taken from a kind of

twilight to the blaze of day. The color of the

stable, therefore, should depend on the quantity

of light. Where much can be admitted, the walls

should be of a gray hue. Where darkness would

otherwise prevail, frequent whitewashing may in

some degree dissipate the gloom.

Grooming.—Of this much need not be said.

The animal that is worked in all weathers needs

little more than a good brushing of his legs. It

is to the stabled horse, highly fed, and irregularly

worked, that grooming is of so much consequence.

Good rubbing with the brush opens the pores of

the skin, circulates the blood and therefore pro

duces a healthy perspiration, and stands in the

room of exercise. No horse will carry a fine

coat without either heat or dressing. They both

effect the same purpose ; they both increase the

insensible perspiration ; but the first does it at

the expense of health and strength, while the

second, at the same time that it produces a glow

on the skin, and a determination of blood to it,

rouses all the energies of the frame. It would

be well for the proprietor of the horse if he were

to insist upon it, and to see that his orders are

really obeyed, that the fine coat he delights in, is

produced by honest rubbing, and not by a heated

stable and thick clothing. When the weather

will permit the horse to be taken out, he should

never be groomed in the stable. Experience

teaches that if the cold is not too great, the ani

mal is invigorated from being dressed in the

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT. 135

open air. inere is no necessity, however, for

half the punishment which many a groom inflicts

upon the horse in the act of dressing; and par

ticularly on one whose skin is thin and sensible.

The currycomb should at all times be lightly ap

plied. With many horses its use may be almost

dispensed with ; and even the brush need not be

so hard, nor the points of the bristles so irregular

as they often are. A soft brush, with a little

more weight of the hand, will be equally effec

tual and a great deal more pleasant to the horse.

A haircloth, while it will seldom irritate and

tease, will be almost sufficient with horses that

have thin hair, and that have not been neglected.

Whoever would be convinced of the benefit of

friction to the horse‘s skin, and to the horse

generally, need only observe the effect produced

by well hand-rubbing the legs of a tired horse.

Every enlargement subsides, the painful stiffness

disappears, the legs attain their natural warmth

and become fine, and the animal is evidently and

rapidly reviving ; he attacks his food with ap

petite, and then quietly lies down to rest.

Exercise.—The work of a farm-horse is usually

regular and not exhausting. He is neither pre

disposed to disease by idleness, nor worn out by

excessive exertion. He has enough to do to

keep him in health, and not enough to distress

or injure him : on the contrary, the regularity of

his work prolongs life. For those who keep a

horse for business or pleasure, the first rule we

would lay down is, that every horse should have

daily exercise. The horse that, with the usual

stable feeding, stands idle for three or four days,

as is the case in many establishments, must suffer.

He is disposed to fever, or to grease, or, most of

all, to diseases of the foot; and if, after these

three or four days of inactivity, he is ridden fast

and far, is almost sure to have inflammation of

the lungs or of the feet.

A road-horse is apt to suffer a great deal more

from idleness than he does from work. A stable-

fed horse should have two hours’ exercise every

day, if he is to be kept free from disease. And

this should be moderate at the beginning and

at the end. Nothing of extraordinary or even

of ordinary labor can be effected on the road

or in the field without sufficient and regular

exercise. It is this alone which can give energy

to the system, or develop the powers of any ani

mal. How then is this exercise to be given ? As

much as possible by, or under the superintendence

of, the owner. The exercise given by any em

ployee is rarely to be depended upon. It is in

efficient, or it is extreme. It is in many cases

both irregular and injurious. It is dependent on

the caprice of him who is performing a task, and

who will render that task subservient to his own

pleasure or purposes.

In training the horse, regular exercise is the

most important of all considerations, however it

may be forgotten in the usual management of

the stable. The exercised horse will discharge

his task, sometimes a severe one, with ease and

pleasure, while the idle and neglected one will

be fatigued ere half his labor be accomplished,

and if he be pushed a little too far, dangerous in

flammation will ensue. How often, nevertheless,

does it happen, that the horse that has stood in

active in the stable three or four days, is ridden

or driven thirty or forty miles in the course of

a single day ? This rest is often purposely given

to prepare for extra exertion ; to lay in a stock

of strength for the performance of the task re

quired of him : and then the owner is surprised

and dissatisfied, if the animal is fairly knocked

up, or possibly becomes seriously ill.

Hay.—The best kinds of hay for horses are the

Timothy, sometimes called Herdsgrass; Orchard

grass; Red-top; and Fowl-meadow. A sweet-

scented vernal grass is common in Northern and

Eastern meadows, and gives the peculiar odor to

new-mown hay so universally admired. A great

part of the hay sold has been pressed and baled,

and in that condition cannot be easily examined;

and if it could, it would even then be hard for

the purchaser exactly to suit himself, supposing

him to know just what is best. For very few

people know how to tell a good from a bad

sample of hay. And yet the characteristics of

good hay are very marked, and such only should

be purchased by the careful horse-owner. Clover

is apt to be dusty, and not properly cured, and

ought not to be fed to horses.

The report of the United States Department

of Agriculture for 1911 estimates that there

were devoted to hay in the United States in

1910, 45,691,000 acres producing 60,978,000

tons valued at $747,769,000; an average to the

acre of 1.33 tons worth $12.26 per ton or

$16.31 per acre. The average farm price of

hay per ton of 2,000 pounds on December 1st,

1904, was $8.72; in 1905, $8.52; in 1906, $10.37;

in 1907, $11.68; in 1908, $8.98; in 1909, $10.62,

and in 1910, $12.26.

Oats.—These with hay constitute what may be

called the standard food of the horse. They

should not be bought by measurement, but by

weight. In Great Britain, a “ prime” sample will

weigh nearly or quite 50 pounds; in the United

States, good oats weigh, say, 35 pounds to the

bushel. A first-rate oat will give three quarters

of its weight in pure grain after the chaff is re

moved ; while a poorer oat gives a less percentage

of solid nutriment. The buyer should be as

careful as to the quality of the oats he buys as to

the quality of his hay. A sound oat should be

I dry and hard ; it should almost chip asunder, and

136

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

not be torn or broken into pieces by compres

sion.

It is estimated that there were devoted to

oats in the United States in 1910, 35,288,000

acres producing 1,126,765,000 bushels valued at

$384,716,000; an average to each acre of 31.9

worth 34.1 cents per bushel or $10.88 per acre.

The great damage done to oats and other cer

eal crops by rusts has been the incentive to

give these diseases further attention. Breed

ing grains for rust resistance is being im

proved by the Department of Agriculture.

Indian Corn.—Next to hay and oats, the most

important food of the horse is corn, or maize.

Corn in the ear should weigh about 70 pounds to

the bushel, and shelled corn about 56. If a pair

of horses require half a bushel of oats a day, they

will require as an equivalent in Indian corn,

half a bushel in the ear, or 28 pounds shelled.

Corn in its natural state is too hard for the teeth

and stomach of many horses, and is a great deal

better for bruising and steaming or softening.

It is estimated that there were devoted to

Indian corn in the United States in 1910, 114,-

002,000 acres, producing 3,125,713,000 bushels,

valued at $1,523,968,000; an average to each

acre of 27.4 bushels, worth 48.8 cents per

bushel, or $13.37 Per acre. The value of the

corn crop in 1910 is more than enough to

cancel the interest bearing debt of the United

States and buy all the gold and silver mined

in all the countries of the earth in 1910.

How, and How Much, to Feed.—What work has the

horse to do ? One kept at slow and exhausting

labor should have three times a day as much

clean, sound grain as he will eat, and as much

clean sweet hay at night as he will consume. In

hot weather the grain should be oats; in winter,

half oats, half corn, with intermediate propor

tions in intermediate weather. For cut feed,

mix with half corn and half oats, ground to

gether, one third the bulk of bran. When the

horses are fed whole grain, this mess is good two

or three times a week, as a change. Farm-horses

should be fed in this way: Give grass at night

when you can instead of hay, but cut the grass

and carry it to the manger; do not turn him out

at night to pasture and make him work to get

his food during the time he ought to be at rest.

Road and pleasure horses should have, in ad

dition to the oats and hay they will eat, a sweet

mash of bran once or twice a week. Don‘t turn

them out to grass. Still, grass in May and early

June, giving a few oats daily with it, is not un-

advisable. Musty or dusty grain ought never to

be fed to horses. It invites heaves and other

disorders. Even washing and kiln-drying will

not cure it.

In the stables of the Third Avenue Railroad

Company, New York, are kept about two thou

sand horses; and according to a very interesting

paper in the St. Nicholas, well worth the reading

of any man or boy, the daily allowance for each

horse is given at twenty-seven pounds of hay,

oats and corn, ground and mixed, equally di

vided into three meals.

When to Feed Horses.—Regularity is as essential

to equine as to human animals. The stomach of

a civilized horse is small, even smaller than that

of his wilder ancestor. Horses that do fast and

exhausting work should be fed grain four times

a day; when at work late in the afternoon or

evening, the last feed should be later than other

wise. Horses are as a rule more apt to undereat

than to overeat; and only when an animal is

gluttonous, should he be restricted in food.

There ought to be an interval of an hour or

more after a meal before a horse is put at work.

After Fasting.—When a horse returns home,

after a long fast, it is most unwise to place the

famished beast before a heaped manger. First

attend to its immediate requirements. These

satisfied, and the harness removed, a pail of gruel

should be offered to the animal. The writer

knows it is said by many grooms that their

horses will not drink gruel; the author likewise

is aware that most servants dislike the bother

attendant on its preparation, while few under

stand the manner in which it should be prepared,

The general plan is to stir a little oatmeal into

any pail containing hot water, and to offer the

mess, under the name of gruel, to the palate which

long abstinence may have rendered fastidious.

The horse only displays its intelligence when it

rejects the potion thus rudely concocted.

Gruel for Horses.—One quart of oatmeal should

be put into a two-gallon pot, which is to be

gradually filled with boiling water, a little cold

being first used, merely to divide the grains. The

saucepan is then placed on the fire, and its con

tents are to be briskly stirred until the liquid has

boiled for ten minutes. After this, it may be put

where it will only just simmer; and in one hour

the gruel will be ready or in shorter time,

should the fire be fierce. The liquid is then

poured through a sieve. The solid part is mingled,

while hot, with an equal quantity of bran, and

this mixture, having been closely covered, is

placed in the manger half an hour after the gruel

has been imbibed.

Hay Tea. —This also is refreshing for a tired

horse. Fill a pail with the best of clean bright

hay, and pour in as much boiling water as the

pail will hold. Keep it covered and hot fifteen

minutes, turn off the water into another pail, and

add a little cold water, enough to make a gallon

and a half or so, and when cold, feed it to the

horse.

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT. 137

Good Mashes.—Boil a couple of quarts of ground

oats, a pint of flax-seed and a little salt, three

hours. Add bran to bring it to a proper con

sistency, and a little molasses. Cover in, and

feed cold.—Another. Moisten four quarts of bran

gradually with hot water, add enough boiling

water to get the proper consistency, add a sprinkle

of salt, cover with a cloth, and feed cold.

Value of a Sieve.—The sieve is not, but ought to

be, in every stable, and to be used freely and

regularly. How much trash gets into baled hay

and grain, useless and even injurious to the

horse! And while the grain remains in the sieve,

after the refuse has been sifted out, it is well to

wash it, either by dipping, or by pouring water

over and through it.

Straw and Trash.—Hay, which the animal re

fuses to touch when placed in the rack, is often

salted and cut into chaff. Thus seasoned, and

in such a shape being mixed with corn, it may

be eaten. The horse is imposed upon by the

salt and the oats which were mingled with the

trash; but has an unwholesome substance been

changed into a wholesome nutriment? It is like

wise a prevailing custom to cut straw of differ

ent kinds and to throw the rubbish into the chaff-

bin. The quadruped may consume this species

of refuse, but such trash distends the stomach

and does not nourish the body. People who ad

vocate cheapness may be favorable to the use

of straw; but these persons should not deceive

themselves, far less ought they to impose upon

others, by asserting that so exhausted a material

can possibly prove a supporting constituent of

diet.

Bread for the Stable.—The action of heat is well

known to change the nature of corn, while fermen

tation converts the starch of the raw seed into

sugar. Might not a coarse kind of bread be made

for the stable ? Such a plan is common through

out Germany, where it is not unusual to see a

carter feeding himself and steed off the same

loaf. The groom might possibly resist such an-

innovation upon his rights and leisure; but a

better order of dependents could be found, to

whom the extra labor would merely prove a pas

time.

Roots.—There are various roots which might

prove very acceptable in the stable. The diges

tion of all such articles is promoted by the

substances being cooked before they are pre

sented. The fire extracts much of the water

with which they all abound ; heat also, in some

measure, arrests the tendency to ferment. Why

should such simple and natural food be denied

to the creature which nature has sent upon this

earth with an appetite fitted to consume it?

There is ample room for choice ; so far as ex-

periment has hitherto tested the value of such

articles of food for horses, results have been ob

tained which seem to say the change should be

generally adopted. A sameness of diet is

known to derange the human stomach. Under

such a system, the palate loses its relish, while a

loathing is excited which destroys appetite.

How often do grooms complain of certain ani

mals being bad feeders! May not such disincli

nation for sustenance be no more than the

disgust engendered by a constant absence of

variety ? Is there any large stable where one or

more quadrupeds are not equally notorious for

being ravenous feeders? The disinclination for

the necessary sustenance and the morbid desire

for an excess of nutriment are alike symptoms of

deranged digestion.

BREEDING AND TRAINING.

Breed for what you Want.—If you propose to

breed a colt or colts, and wish to do it as intelli

gently as your opportunities will allow, settle at

the beginning what you want, whether a runner,

a trotter, a roadster, or whatever it is, and act

accordingly. Progeny will inherit the qualities,

or the mingled qualities, of the parents, using the

word parents to include ancestry. Diseases, or

a predisposition to them, are inherited among

horses as certainly as among humans. So are

peculiarities of form and of constitution ; and it

is necessary, if any definite and clear result be

hoped for with reason, that sire and dam be se

lected with a definite aim definitely carried out.

If you only wish to take your chances for a com

mon everyday horse, breed from the best sires

you can find, and try to select such characteris

tics as will promise the highest results when

combined with those of your mare.

Don‘t begin at too early an age. A mare is

capable of breeding at three or four years old.

Do not commence, as some have done, at two

years, before her form or her strength is suffi

ciently developed, and with the development of

which this early breeding will materially inter

fere. To get excellence in the offspring, you

must have the highest development in the par

ents; and degeneration will certainly result if im

mature animals are bred from. And don’t keep

the mare breeding when she has become too old,

or has broken down. If she does little more

than farm work, and is reasonably treated at

that, she may continue to be bred from until she

is nearly twenty; but if she has been hardly

worked, and bears the marks of it, let her have

I been what she will in her youth, she will be

likely to deceive the expectations of the breeder

in her old age. People do not seem to conceive

that there can be any outrage committed by

breeding from the body which, through a life of

service, has earned a right to rest, But many

138 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

proprietors only “ throw up” the animal they in

tend should perpetuate its race, after strains and

pains have rendered longer life a misery.

Exercise.—In the case of both the sire and the

mare, the extremes of idleness and of overwork

should be alike avoided. The stallion should be

in the best condition for his office: should not

be confined in a warm dark stable, with insuffi

cient work, allowed to get too fat, and then be ex

pected to impress on his progeny the good qua

lities he ought to transmit. And the dam, for the

whole period of gestation, ought to be kept at

moderate work. Idleness, high living, and too

much flesh work mischief to her and her off

spring, as certainly as they do to her fellow-

mammais, highest in the scale of being. Per

haps the more common danger may lie in the

direction of too much, not too little, exercise and

insufficient food ; but if the best results are to be

obtained, the judicious middle course must be

taken. In horses, as in the human family, per

fect health involves the constant and judicious

use of the muscles, and the consequent uniform

and thorough vitalization of the blood, by which

only can the best results be obtained from

mother or offspring.

Breeding in and in.—On this subject, that is,

persevering in the same breed, and selecting the

best on either side, much has been said. The

system of crossing requires much judgment and

experience; a great deal more indeed than

breeders usually possess. The bad qualities of

the cross are too soon engrafted on the original

stock, and once engrafted there, are not, for

many generations, eradicated. The good ones of

both are occasionally neutralized to a most mor

tifying degree. On the other hand, it is the fact,

however some may deny it, that strict confine

ment to one breed, however valuable or perfect,

produces gradual deterioration. The truth here,

as in many other cases, lies in the middle ; cross

ing should be attempted with great caution, and

the most perfect of the same breed should be

selected, but varied, by being frequently taken

from different stocks.

Proper Time.—The mare comes into heat in the

early part of the spring. She is said to go with

foal eleven months, but there is sometimes a

strange irregularity about this. Some have been

known to foal five weeks earlier, while the time

of others has been extended six weeks beyond

the eleven months. We may, however, take

eleven months as the average time. In running-

horses, that are brought so early to the starting-

post, and whether they are foaled early in Janu

ary or late in April, rank as of the same age, it is

of importance that the mare should go to cover as

early as possible : in a two or three-year-old, four

months would make considerable difference in

the growth and strength; yet many of these

early foals are almost worthless, because they

have been deprived of that additional nutriment

which nature designed for them. For other

breeds, the beginning of May is the most con

venient period. The mare would then foal in

the early part of April, when there would begin

to be sufficient food for her and her colt, withou\

confining them to the stable.

Abortion.—From the fourth month, the mare

should have a little better food. This is about

the period when there is danger of abortion, or,

as it is technically called, “slinking the foal;”

at this time, therefore, the eye of the owner

should be frequently upon her. Good feeding

and moderate exercise will be the best preven

tives against this. The mare that has once

slinked her foal is ever liable to the same acci

dent, and therefore should never be suffered to

be with other mares near the time of danger.

She should be kept away from bad smells, should

not be allowed to see blood or dying animals, and

she should never be frightened. Keep her quiet

and as contented as may be, and see that she

has plenty of food and of fresh air, and due exer

cise.

Indications of Foaling Time.—From one to three

months before the expected event, the udder be

gins to fill and swell, and continues increasing.

Some three weeks before, a hollow begins to ap

pear on each side the spinal extension, reaching

from the haunch to the tail, and becomes more

apparent as the time approaches. The udder

two days before, or even less, will exude a gum

my substance from the end of each teat.

Foaling.—When the time comes, the mare will

not be long in labor. She should be led into a

thickly littered loose box, with plenty of straw,

and without interstices through which she can

get her legs. As a general thing, she needs no

assistance. Where a false presentation is made,

or the size of the coming foal demands it, mechan

ical services may be needed. The foal requires

nothing beyond a sheltered abode and its mo

thers attention. If it does not get milk enough

within twenty-four hours, a little skimmed cows’

milk, first boiled and then slightly sweetened,

being afterward diluted with its amount of warm

water, may, when sufficiently cool, be presented.

The human hand is inserted in the fluid, and two

fingers only allowed to protrude above the sur

face; these are generally seized upon, the nour

ishment being easily imbibed by the hungry foal.

More than a single feed is seldom needed.

The Mare and Colt—The colt should run with

its mother for five or six months, when it should

be weaned. The mare should from the start

have plenty of grass, and enough else to keep

her in condition, On weaning the colt, the mare

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT.

139

should be put on dry food to reduce the flow,

and if necessary the milk be drawn off by hand.

The mare will usually be found in heat at or

within a month from the time of foaling, when,

if further immediate breeding is an object, she

may be put again to horse.

The Young Colt.—He should be liberally fed

during the whole of his growth. Bruised oats

and bran should form a considerable part of his

daily provender. Money expended on the proper

nourishment of the growing colt is well laid

out, but he should not be rendered delicate by

excess of care. He should be daily handled,

partially dressed, accustomed to the halter, led

about, and even tied up.

TRAINING HORSES.

Rarey’s Directions.—Remember that there are

certain natural laws that govern the horse. It

is natural for him to kick whenever he gets badly

frightened ; it is natural for him to escape from

whatever he thinks will do him harm. His fac

ulties of seeing, hearing and smelling have been

given him to examine everything new that he is

brought into contact with. And as long as you

present him with nothing that offends his eye,

nose or ears, you can then handle him at will,

notwithstanding he may be frightened at first,

so that in a short time he will not be afraid of

anything he is brought in contact with. All of

the whipping and spurring of horses for shying,

stumbling, etc., is useless and cruel. If he shies,

and you whip him for it, it only adds terror, and

makes the object larger than it would otherwise

be; give him time to examine it without punish

ing him. He should never be hit with the whip,

under any circumstances, or for anything that he

does. As to smelling oil, there is nothing that

assists the trainer to tame his horse better. It

is better to approach a colt with the scent of

honey or cinnamon upon your hand, than the

scent of hogs, for horses naturally fear the scent

of hogs, and will attempt to escape from it,

while they like the scent of honey, cinnamon or

salt. To affect a horse with drugs, you must

give him some preparation of opium, and while

he is under the influence of it, you cannot teach

him anything more than a man when he is in

toxicated with liquor. Another thing, you must

remember to treat him kindly, for where you re

quire obedience, it is better to have it rendered

from a sense of love than fear.

“ You should be careful not to chafe the lips

of your colt or hurt his mouth in any way; if

you do, he will dislike to have the bridle on.

After he is taught to follow you, then put on the

harness, putting your lines through the shaft-

straps along the side, and teach him to yield to

the reins, turn short to the right and left, teach

him to stand still before he is ever hitched up ;

you then have control over him. If he gets

frightened, the lines should be used as a tele

graph, to let him know what you want him to

do. No horse is naturally vicious, but always

obeys his trainer as soon as he comprehends

what he would have him do ; you must be firm

with him at the same time, and give him to

understand that you are the trainer, and that he

is the horse.

“The best bits to be used to hold a horse, to

keep his mouth from getting sore, is a straight

bar-bit, 4½ inches long between the rings; this

operates on both sides of the jaw, while the

ordinary snaffle forms a clamp and presses the

side of the jaw. The curb or bridoon hurts his

under jaw so that he will stop before he will give

to the rein.

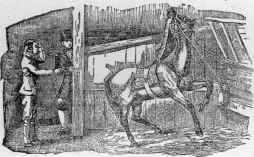

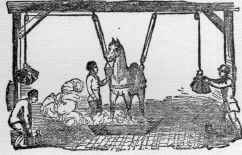

To Throw a Horse.

“To throw a horse, put a rope 12 feet long

around his body in a running noose, pass it down

to the right forefoot through a ring in a spancil,

then buckle up the left or near forefoot, take a

firm hold of your rope, lead him around until he

is tired, give him a shove with your shoulder, at

the same time drawing up the right foot, which

brings him on his knees, hold him steady, and

in a few moments he will lie down. Never at

tempt to hold him still, for the more he scuffles

the better.

“Take your colt into a tight room or pen,

and with a long whip commence snapping at his

hind leg, taking care not to hit above the hocks,

stopping immediately when he turns his head

towards you; while his head is towards you, ap

proach him with the left hand extended toward

him, holding your whip in the right, ready to

snap him as soon as he turns his head from you.

In this way you can soon get your hands upon

140 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

him. As soon as you have done this, be careful

to caress him for his obedience, and snap him

for his disobedience. In this way he will soon

learn that he is safest in your presence with his

head towards you, and in a very short time you

cannot keep him away from you. Speak kindly

and firmly to him, all the time caressing him,

calling by name, and saying, ‘ Ho, boy,’ or ‘ Ho,

Dan,’ or some familiar word that he will soon

learn.

“ If a colt is awkward and careless at first,

you must bear with him, remembering that we,

too, were awkward when young; allowing him

his own way, until by degrees he will come in. If

he is willful, you must then change your course

of treatment, by confining him in such a way

that he is powerless for harm until he submits.

If he is disposed to run, use my pole-check on

him ; if to kick, fasten a rope around his under

jaw, pass it through the collar and attach it to

his hind feet. In this way one kick will cure

him, as the force of the blow falls on his jaw. If

he should be stubborn, lay him down and con-

fine him until you subdue him, without punish

ing him with the whip.

“ Colts should be broken without blinds; after

they are well broken, then you may put them

on. Bridles without blinds are the best, unless

you want to speed your horse: then it will be

necessary to keep him from seeing the whip.

Colts should be well handled and taught to give

readily to the rein before they are hitched up.

If you hitch them up the first thing and they be

come frightened, then you have no control over

them ; but if you teach them to start, stop and

stand at the word before they are hitched, then

you can govern them.”

“Breaking” Horses.—The notion of “breaking”

a horse is disappearing. A few years ago, the

general feeling was, that a horse must be sub

dued, have his “will broken,” and be made to

understand, once for all if possible, that he must

implicitly obey. Under this system, resting im

mediately and undisguisedly on brute force,

the animal, its spirit broken, perhaps be

came an automaton, performing through fear

what resistance could not save him from. If he

tried to avoid a strange object that frightened

him, the whip, the spur and equally torturing

shouts were applied, and perhaps he succumbed,

and perhaps he didn’t. Sometimes the superior

force of the animal won, he became or was re

garded as vicious and tricky, and was sold from

hand to hand, till a horse fit for Gen. Grant to

ride or drive, sank to an omnibus or the towpath

of the canal. Mr. Rarey‘s success in training

horses brought into immediate notice a much

better way, and the increasing spirit of humanity

has carried forward what he was so prominent

in introducing. With horses as with men, the

great majority may be trained from higher im

pulses than mere fear, and may be brought to a

stage of cooperative confidence and helpfulness

impossible where mere brute force is the sole

appeal.

TRAINING THE COLT.

This process should commence from the very

period of weaning. The foal should be daily

handled, partially dressed, accustomed to the

halter, led about, and even tied up. The tracta-

bility, good temper and value of the horse de

pend greatly upon this. These offices should be

performed as much as possible by the man by

whom the colt is fed, and whose management

should be always kind and gentle. There is no

fault for which a servant should be discharged

so invariably or so promptly as cruelty, or even

harshness, toward young stock ; for the principle

on which their later usefulness is founded, is

early attachment to and confidence in man, and

the implicit obedience resulting principally from

these.

After the second winter, the work of training

may begin in earnest. He may first be bitted,

and with a bit smaller than usual, and that will

not hurt his mouth ; with this he maybe allowed

to amuse himself and to play, and to champ for

an hour on a few successive days.

If he is destined for farm or wagon work, por

tions of the harness may, after he has become a

little tractable, be put on him, and last of all the

blinds. Let his first trial be by the side of an

other horse, and before an empty wagon. Give

him an occasional pat or kind word; and in a

little while he will learn to pull, when a load may

be given him, and gradually increased.

When he begins a little to understand his busi

ness, backing, the most difficult part of his work,

may be taught him ; first to back well without

anything behind him, then with a light cart, and

afterwards with some definite load ; and taking

the greatest care not to seriously hurt the mouth.

If the first lesson causes much soreness of the

gums, the colt will not readily submit to a

second. If he has been rendered tractable be

fore by kind usage, time and patience will do all

that can be wished here. Blinding him may be

necessary with a restive and obstinate colt, but

should be used only as a last resort.

The same principles will apply to the training

of the horse for the road or the track. The

handling, and some portion of instruction, should

commence from the time of weaning. The

future tractability of the horse will much de

pend on this. At two and a half or three years

the regular proccss of training should come on.

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT.

141

If it be delayed until the animal is four years

old, his strength and obstinacy will be more

difficult to overcome. There should be much

more kindness and patience, and far less harsh

ness and cruelty, than are often exhibited, and a

great deal more attention to the form and natural

action of the horse. A headstall is put on the

colt, and a cavesson (or apparatus to confine and

pinch the nose) affixed to it, with long reins. He

is first accustomed to the rein, then led round a

ring on soft ground, and at length mounted and

taught his paces. Next to preserving the temper

and docility of the horse, there is nothing of so

much importance as to teach him every pace,

and every part of his duty, distinctly and tho

roughly. Each must constitute a separate and

sometimes long-continued lesson, and that taught

by a man who will never suffer his passion to

get the better of his discretion.

After the cavesson has been attached to the

headstall, and the long rein put on, the first

lesson is, to be quietly led about by the trainer,

a steady boy following behind, by occasional

threatening with the whip, but never by an

actual blow, to keep the colt up. When the

animal follows readily and quietly, he may be

taken to the ring, and walked round, right and

left, in a very small circle. Care should be taken

to teach him this pace thoroughly, never suffer

ing him to break into a trot. The boy with his

whip may here again be necessary, but not a single

blow should actually fall.

Becoming tolerably perfect in the walk, he

should be quickened to a trot, and kept steadily

at it; the whip of the boy, if needful, urging him

on, and the cavesson restraining him. These

lessons should be short. The pace should be

kept perfect and distinct in each ; and docility

and improvement rewarded with frequent ca

resses, and handfuls of corn. The length of the

rein may now be gradually increased, the pace

quickened, and the time extended, until the ani

mal becomes tractable in these his first lessons,

towards the conclusion of which, crupper-straps,

or something similar, may be attached to the

clothing. These, playing about the sides and

flanks, accustom him to the flapping of the coat

of the rider. The annoyance which they occa

sion will pass over in a day or two; for when the

animal finds that no harm comes to him on

account of these straps. he will cease to regard

them.

Next comes the bitting. The bit should be

large and smooth, and the reins should be

buckled to a ring on either side of the pad. The

reins should at first be slack, and very gradually

tightened. This will prepare for the more per

fect manner in which the head will be afterward

got into a proper position, when the colt is

accustomed to the saddle. Occasionally the

trainer should stand in front of the colt, take

hold of each side-rein near the mouth, and press

upon it, and thus begin to teach him to stop and

to back at the pressure of the rein, rewarding

every act of docility, and not being too eager to

punish occasional carelessness or waywardness.

The colt may now be taken into the road or

street to be gradually accustomed to objects

among which his services will be required.

Here, from fear or playfulness, a considerable

degree of starting and shying may be exhibited.

As little notice as possible should be taken of it.

The same or similar objects should be soon

passed again, but at a greater distance. If the

colt still shies, let the distance be farther in

creased, until he takes no notice of the object ;

then he may gradually be brought nearer to it,

and this will be usually effected without the

slightest difficulty; whereas, had there been an

attempt to force the animal close to it in the

first instance, the remembrance of the contest

would have been associated with the object,

and the habit of shying would have been es

tablished.

Hitherto, with a cool and patient trainer, the

whip may have been shown, but will scarcely

have been used ; the colt must now, however, be

accustomed to this necessary instrument of

authority. Let the trainer walk by the side of

the animal, and throw his right arm over his

back, holding the reins in his left, and occasion

ally quicken his pace, and, at the moment of

doing this, tap the horse with the whip in his

right hand, and at first very gently. The tap of

the whip and the quickening of the pace will

soon become associated together in the mind of

the animal. If necessary, the taps may gradu

ally fall a little heavier, and the feeling of pain

be the monitor of the necessity of increased

exertion. The lessons of reining-in and stop

ping, and backing on the pressure of the bit,

may continue to be practiced at the same time.

He may now be taught to bear the saddle.

Some little caution will be necessary at first

putting it on. The trainer should stand at the

head of the colt, patting him and engaging his

attention, while an assistant on the off-side

gently places the saddle on the animal‘s back,

and another on the other side slowly tightens

the girths. If he submits quietly to this, as he

generally will when the previous training has

been properly conducted, the operation of mount

ing may be attempted. The trainer will need

two assistants. He will remain at the colt‘s head,

patting and fondling him, while the rider will

put his foot into the stirrup and bear a little

weight on it, while the man on the off side

| presses equally on the other stirrup-leather; and

142

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

according to the docility of the animal, he will

gradually increase the weight until he balances

himself on the stirrup. If the colt be uneasy or

afraid, he should be spoken kindly to and patted,

or a mouthful of corn be given him ; but if he

offer serious resistance, the training must ter

minate for that day ; he may be in better humor

on the morrow.

When the rider has balanced himself for a

minute or two, he may gently throw his leg over,

and quietly seat himself in the saddle. The trainer

will then lead the animal round the ring, the

rider sitting perfectly still. After a few minutes

he will take the reins and handle them as gently

as possible, and guide the horse by the pressure

of them; patting him frequently, and especially

when he thinks of dismounting, and after hav

ing dismounted offering him a little corn. The

use of the rein in checking him, and of the

pressure of the leg and the touch of the heel

in quickening his pace, will soon be taught, and

the education will be nearly completed.

The horse having thus far submitted himself

to the trainer, these pattings and rewards must

be gradually diminished, and implicit obedience

mildly but firmly enforced. Severity will not

often be necessary; in the great majority of

cases it will be altogether uncalled for; but

should the animal waywardly dispute the order

of the trainer, he must at once be taught that

he is the servant, and must obey. The educa

tion of the horse is much like that of the child.

Pleasure is, as much as possible, associated with

the early lessons; but firmness or, if needed,

coercion must confirm the habit of obedience.

Tyranny and cruelty will, more speedily in the

horse than in the child, provoke the wish to dis

obey, and the resistance to command. The

restive and vicious horse is, in ninety-nine cases

out of a hundred, made so by ill-usage. None

but those who will take the trouble to try the

experiment are aware how absolute a command

a due admixture of firmness and kindness will

soon give over any horse.

The Check-Rein.—There has been great outcry

made against the use of this rein, here and also

in England, where it is called the bearing-rein.

Mr. Bergh has denounced its use vehemently,

and as President of the “ Society for the Preven

tion of Cruelty to Animals” has tried to force

its banishment. To check-rein a horse is said

to be equivalent to trussing a man’s head back

ward toward his back or heels, and compelling

him, while in this position, to do duty with a

loaded wheelbarrow. Mayhew says: “ For the

rapid motion of the head being impossible, it

cannot be used to restore the disturbed balance.

The nimbleness which could avoid sudden dan

ger is destroyed by the fashionable want of feel

ing. It is a matter for surprise that the presence

of the bearing-rein is never alluded to when gen

tlemen seek redress because their vehicles have

been damaged. Most horsemen, however, es

teem the neck for its appearance, and few com

prehend its utility.”

And Youatt: " The angles of the lips are fre

quently made sore or wounded by the smallness

or shortness of the snaffle, and by the unneces

sary and cruel tightness of the bearing-rein.

This rein not only gives the horse a grander ap

pearance in harness, and places the head in that

position in which the bit most powerfully presses

upon the jaw, but there is no possibility of driv

ing without it, unless the arm of the driver is as

strong as that of Hercules; and most certainly

there is no safety if it be not used. There are

few horses who will not bear, or bore upon some

thing, and it is better to let them bore upon

themselves than upon the arm of the driver.

Without this control, many of them would hang

their heads low and be disposed every moment

to stumble, and would defy all pulling, if they

tried to run away. There is, and can be, no ne

cessity, however, for using a bearing-rein so tight

as to cramp the muscles of the head, which is

indicated by the animal’s continually tossing up

his head : they may indeed be cramped to such

a degree, that the horse is scarcely able to bring

his head to the ground when turned to grass.

The tight rein injures and excoriates the angles

of the lips, and frequently brings on poll-evil.

Except it be a restive or determined horse,

there should be little more bearing upon the

mouth than is generally used in riding. This

the horse likes to feel, and it is necessary for

him in the swift gallop. We must have the bear

ing-rein, whatever some men of humanity may

say against it; but we need not use it cruelly.”

This seems to be the conclusion of common-

sense. Sentimentalists may condemn and de

nounce the check-rein. Now and then a horse gets

along without it. So “ reformers” occasionally

condemn and denounce the use by women of cor

sets or stays, and now and then a woman gets

along without them. In Greece and Rome per

haps neither device was used. But here and now,

in the great majority of instances, it is safer and

pleasanter to use a check-rein in driving.

THE TEETH.

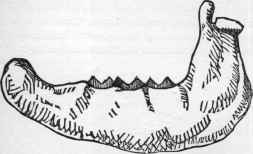

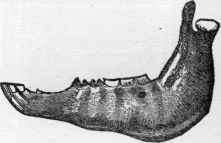

A foal at birth has three molars, or grinding-

teeth, just through the gums, upon both sides

of the upper and of the lower jaws. It generally

has no incisors or front teeth; but the gums are

inflamed and evidently upon the eve of bursting.

The molars or grinders are, as yet, unflattened

or have not been rendered smooth by attrition.

HORSES AND THEIR MANAGEMENT. 143

The lower jaw, when the inferior margin is felt,

appears to be very thick, blunt and round.

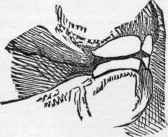

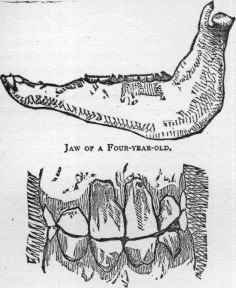

A fortnight has rarely elapsed before the

membrane ruptures, and two pairs of front, very

white teeth begin to appear in the mouth. At

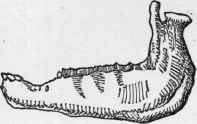

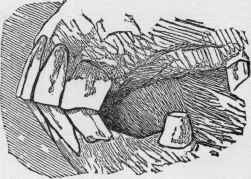

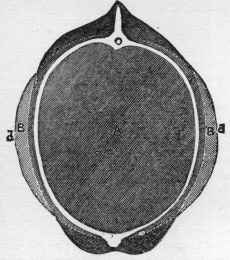

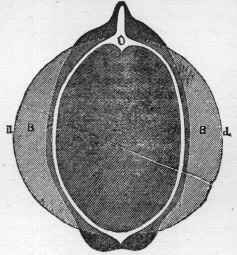

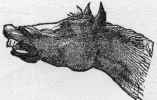

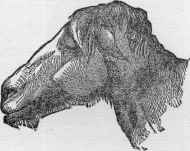

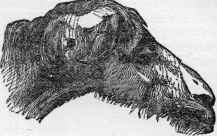

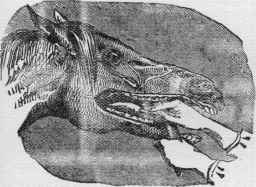

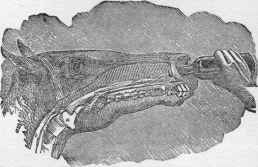

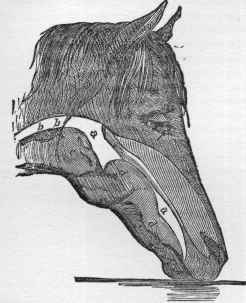

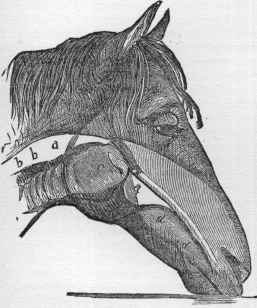

The Foal’s Jaw at Birth.

first, these new members look disproportionately

large to their tiny abiding-place ; and when con

trasted with the reddened gums at their base,

they have that pretty, pearly aspect which is the

common characteristic of the milk teeth in most

animals.

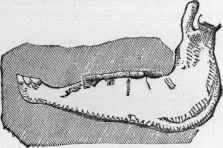

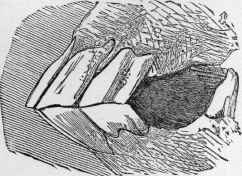

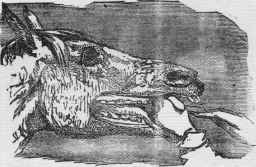

The Incisors at Two Weeks Old.

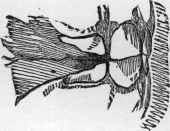

In another month, when the foal is six weeks

old, more teeth appear. Much of the swelling

at first present has softened down. The mem

brane, as time progresses, will lose much of its

scarlet hue. In the period which has elapsed

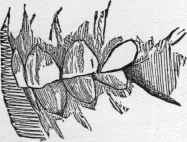

The Incisors at Six Weeks Old.

since the former teeth were looked at, the sense

of disproportionate size has gone. The two

front teeth are now fully up, and these are al

most of suitable proportions. When the two

pairs of lateral incisors first make their appear

ance, it is in such a shape as can imply no assur

ance of their future form. They resemble the

corner nippers, and do not suggest the smallest

likeness to the lateral incisors which they will

ultimately become.

There is now a long pause before more teeth

appear. The little one lives chiefly upon suction,

and runs by its mother‘s side. Upon the com

pletion of the first month, seldom earlier, it may

be observed to lower its head and nip the young

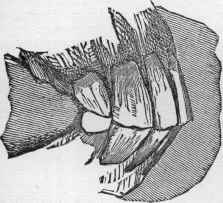

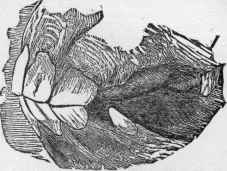

grass. From the third month, however, the

habit grows, until, by the sixth month, the grind

ers will be worn quite flat, and have been re

duced to the state suited to their function.

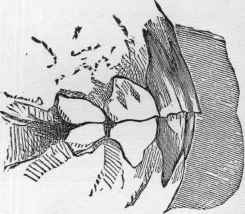

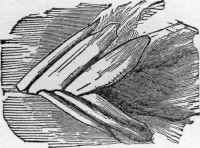

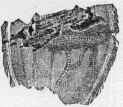

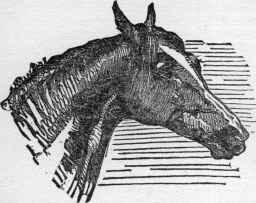

The Front Teeth at Nine Months Old.

The corner incisors come into the mouth about

the ninth month, the four pair of nippers, which