264 “ THE FRIEND OF ALL.

SHEEP AND THEIR VARIETIES

Breeds, Principal:

American Merinos.................264

Black-faced Heath.................266

Cheviot............................265

Cotswolds.........................264

Devonshire Notts..................264

Moorland Sheep of Devonshire... 270

Hampshire-Down.................. 264

Leicester, Old......................264

Leicester, New or Border..........265

Lincolnshire, Old..................264

Oxford-Down......................264

Rocky Mountain...................265

Breeds, Principal:

Romney Marsh.....................264

Shetland Sheep....................266

South-Down........................263

Shropshire-Down..................264

Diseases of Sheep....................268

Domestication, Early................ 262

Industrial Importance................262

Rearing and Keeping................266

Feeding, Winter..................267

Insects, Protection from...........267

Lambing Time.....................266

Lambs, Weaning...................266

Rearing and Ke eping:

Marking........................... 267

Pasturage..........................266

Pastures, Early and Late...........267

Rutting............................266

Water..............................267

Weeds, Fondness of Sheep for......267

Shearing.............................267

Washing............................267

Sheep-Husbandry, and Statistics......263

in United States... 263

Tying the Wool.......................268

Varieties of the Sheep................263

Early Domestication.—There can be little doubt

that sheep were the earliest domesticated animals.

Abel, the second son of Adam, was a keeper of

sheep, and the pastoral life was the favorite occu

pation of man in the early ages, agriculture being

followed from necessity rather than from choice.

The antiquity of their domestication is further

proved by their widely diversified character ; the

Linnæan classification giving the Hornless, Horn

ed, Black-faced, Spanish, Many-horned, African,

Guinea, Broad-tailed, Fat-rumped, Bucharian,

Long-tailed, Cap-bearded and Bovant. In addi

tion to these are the Siberian sheep of Asia,

found also in Corsica and Barbary, and the

Cretan sheep of the Grecian Islands, Hungary

and some portions of Austria, which are about

all the princioal sub-soecies,

Industrial Importance.—Sheep were the chief ele

ment of wealth among the Hebrew patriarchs;

and the Latin term perns (cattle), whence was de

rived pecunia (wealth), was especially applied to

them. In ancient times they were bred mainly

for their skins and milk, the latter abundant,

agreeable and very nourishing. Now they are

prized chiefly for their wool, flesh and fat. Mut

ton, as is well known, is the most highly nutri

tious of all flesh meats, and the demand for it is

steadily increasing. To supply the markets of

New York City alone more than a million sheep

per annum are needed. Farmers, hitherto daily

consumers of pork, are becoming eaters of mut

ton, and the convenience of keeping a few sheep

merely to supply the family table is appreciated

as never before,

SHEEP. 265

Sheep-Husbandry, and Statistics.—In Great Bri

tain the breeding and feeding of sheep has been

second in importance only to that of cattle.

Since the settlement of Australia and the other

British dependencies, the rearing of fine-wooled

sheep, however, has been almost entirely aban

doned, sheep-raisers confining themselves main

ly to the breeding of long, medium- and short-

wooled sheep—valuable as well for mutton as for

their fleeces—leaving to the United States and

to the British colonies the almost exclusive

rearing of fine-wooled sheep—Saxony, Silesian,

and French and Spanish Merinos. This produc

tion has grown vastly, as these Merinos may be

kept in immense flocks, and because, as every

body knows, in Australasia and in Texas, New

Mexico, and the great American plains east of

the Rocky Mountains, there are vast ranges of

country where stock of all kinds may be herded

at a minimum cost.

Last year (1882) the sheep of the world were es

timated to be 600,000,000 head, yielding 2,000,000,-

ooo pounds of wool annually. Of this number

Great Britain had 35,000,000 sheep, shearing

218,000,000 pounds of wool annually. This wool

is mainly of long, middle and short staple, but

is not fine wool. The rough wool, medium fine

to coarse, but not uniform in its texture, is pro

duced in South America and Mexico from 58,-

000,000 sheep, yielding annually 174,000,000

pounds of wool; in North Africa, with 20,000,-

ooo sheep, yielding 45,000,000 pounds ; and in

Asia, with 175,000,000 sheep, yielding annually

350,000,000 pounds of wool. Now if we add to

these numbers 25,000,000 sheep for the moun

tainous and northern regions of Europe, Greece

and Turkey, and 50,000,000 for Russia, producing

in all 164,000,000 pounds of wool, the remaining

portions of the world may be set down as the

home of fine-wooled sheep. Of these Australia

has 60,000,000; the United States, 36,000,000;

the Cape of Good Hope, 12,000,000; Germany,

29,000,000 ; Austro-Hungary, 21,000,000 ; France,

26,000,000 ; Spain, 22,000,000 ; Italy, 11,ooo,ooo;

Portugal, 2,750,000 sheep. Of all these coun

tries, Australia produces the finest wool, while

the United States and Canada come next, al

though Canada is essentially a mutton-producing

country, which the United States is not, for the

number of sheep kept.

In the United States.—Notwithstanding the vast

territory in the United States adapted to sheep-

husbandry, the industry has not kept pace with

the demand, and until about ten years ago our

wool imports were constantly increasing in spite

of the yearly increment of our flocks. From 1870

to 1875 only two thirds of our manufactured wool

product was home grown. Since that time our

annual imports have not increased. The bulk

of imported wool is of low-grade carpet-wools

and unwashed Merino, and constituting only one

fourth of the product manufactured.

VARIETIES OF THE SHEEP.

The numerous varieties of sheep that now exist

in different parts of the globe have all been re

duced by Cuvier into four distinct species : 1.

Ovis Ammon—the Argali. This species is re-

markable for its soft reddish hair, a short tail,

and a mane under its neck. It inhabits the rocky

districts of Barbary and the more elevated parts

of Egypt. 2. Ovis tragelaphus—the bearded

sheep of Africa. 3. Ovis musmon—the Musmon

of Southern Europe. 4. Ovis montana—the Mou-

flon of America; but this species, which inhabits

the Rocky Mountains, is now believed to be

identical with the Argali, which frequents the

mountains of Central Asia, and the higher plains

of Siberia northward to Kamtchatka. This

leaves only three distinct species of wild sheep as

yet discovered.

It is still a point in dispute from which of these

races our domestic sheep have been derived ; nor

is the question of great practical importance,

though its solution is very desirable in a phy

siological point of view. Whether the wild races

may be regarded as of one species, as some natu

ralists contend, or of different species, according

to others, the best judges are next to unanimous

that the domestic races are of one species ; and

what are called different breeds are nothing more

than varieties, the result of different culture, food

and climate.

PRINCIPAL BREEDS.

Among the principal breeds reared in Great

Britain and the United States are the following;

South-Down Sheep.—Of this variety the Chicago

Breeder's Gazette thus speaks:

“ Wherever symmetry in outline and perfection

in detail are appreciated, the South-Down stands

the peer of domestic animals of any breed. With

an origin beyond the sweep of history, its merits

as a flesh-producing animal have had special

recognition for more than a century, during

which time it has been so bred within its own

blood as to perfect and intensify its best features,

while being employed for the improvement of

many other types claiming popular favor. Its

flesh has long been deemed the synonym of per

fection in its line—the ambition of fanciers of

other types rarely extending beyond the stan

dard of South-Down mutton. As a meat-producer

the South-Down has in its favor all of the recog

nized requisites: 1. Precocity—its deep chest

and rounded rib insuring the fullest play of the

vital organs ; 2. Prolificacy—flocks wherein the

lambs outnumber the ewes being by no means un-

266 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

common ; 3. Propensity to thrive under average

conditions—being ready for market at any time

from six weeks old to maturity; 4. Prepotency—

its long years of pure breeding having so inten

sified its characteristics as to insure them pro-

South-Down Ram.

minence when crossed with other breeds ; 5.

Hardiness—it being found to thrive well under

such treatment as the average farmer usually de

votes to his stock.”

Oxford, Shropshire and Hampshire-Downs.—These

breeds attain a much larger size than the original

South-Downs, and also carry heavier fleeces. It

Is supposed that this has been attained by a cross

of the South-Downs with Lincolnshire or Cots-

wold blood ; be that as it may, they are now

acknowledged as separate breeds of great value,

combining the finest mutton with a heavy and

valuable fleece ; but certainly the Shropshire and

Hampshire-Downs are deficient in form. The

cultivation of the Oxford-Downs, in particular, is

rapidly spreading, and likely to extend in all low-

(ying districts where pure flocks are raised simply

for the butcher-market.

American Merinos.—To quote again from the

Breeders Gazette: “Probably three fourths of

;he now nearly fifty million sheep in the United

Group of American Merinos.

States have a certain proportion of Merino blood

in their veins. For eighty years the importations |

of Spanish Merinos made between 1800 and

1812 have had especial interest for American

breeders, who found in the improvement of fleece

and carcass opportunity for displaying their

highest skill in breeding and management.

Their success in these respects has been such

that the typical American Merino—(properly

called American, because it is as distinct from

the type of its Spanish progenitor, and as fixed

in its characteristics, as the French, or Saxony,

or Australian types)—possesses every needed re

quisite for a profitable flocking sheep. Where

so many eminent breeders have achieved suc

cesses, when so many localities are justly noted

for the excellence of their flocks, the day has gone

by for any man or any State to consistently claim

pre-eminence in the superiority of its flocks.

Money and enterprise have scattered flocks from

the Eastern States, where the importations of

fourscore years ago were cradled and brought into

general prominence, until today animals of the

highest individual excellence are to be found

West and South, as well as East.”

There are three families of American Merinos

—the Atwood, the Rich and the Hammond.

The Merinos are not so much prized for their

flesh as for their wool, which has a fineness and

felting quality not found in other breeds, and

weighs heavier. Shearing is a yearly operation,

and eating is final. The sheep that shears ad

vantageously is, therefore, the most profitable,

and in that respect, there is not a question as to

the claims of the Merino.

Cotswolds.—This breed has been long raised on

the Cotswold Hills in Gloucestershire, and is

abundant in the fertile valleys of South Wales. It

possesses long open wool, and is among the largest

sheep in the United Kingdom. Of all English

breeds it is the variety most widely disseminated

in the United States. It is hardy and mode

rately early in maturing ; strong in constitution ;

broad-chested ; round-barreled ; straight-backed ;

and fattens kindly at thirteen to fifteen months

old to yield 15 pounds of mutton per quarter.

The wool is rather strong and coarse, but white

and mellow, 6 to 8 inches in length, and averag

ing 7 to 8 pounds per fleece : some American

fleeces have been sheared weighing 18 pounds.

It is valued for its mutton, the lean meat being

large in proportion to the fat. It is used to some

extent in crossing ewes of smaller breeds, for

raising feeding-stock or lambs for the butcher.

The Devonshire Notts, Romney Marsh, Old Lincoln

shire, Teeswater and Old Leicester Sheep.—There

are two varieties of the Devonshire Notts : one

is called the Dun-faced Notts, from the color of

the face ; this is a coarse animal, with flat ribs

and crooked back but it yields a fleece weighing

10 pounds, and when fat weighs 22 pounds per

SHEEP.

267

quarter when only thirty months old. The sec

ond variety is called the Bampton Notts ; it re

sembles the former in many respects, but is

easier fed, yields less wool, and has the face and

legs white.

The Romney Marsh breeds are very large ani

mals, with white faces and legs, and yield a

heavy fleece, the quality good of its kind. Their

general structure is defective, the chest being

narrow and the extremities coarse. The result

of their being crossed by the New Leicester is

still a point in dispute—one party alleging that,

though the quantity of wool has been lessened

and the size of the animal diminished by the

cross, the tendency to fatten and the general

form have been much improved. On the other

hand, some well-informed breeders contend

that, besides the loss of the quantity and quality

of the wool, the constitution of the animal is

rendered less fitted to the cold and marshy pas

tures on which it feeds.

The Old Lincolnshire breed are large, coarse,

ill-shaped, slow feeders, and yield indifferent

mutton, but a fleece of very heavy long wool.

The Teeswater breed were originally derived

from the preceding, and pastured on the rich

lands in the valley of the Tees, from which they

derive their name ; but Professor Low remarks

that “ it is entirely changed by crossing with the

Dishly breed, and that the old unimproved race

of the Tees is now scarcely to be found.” They

are very large, and attain a greater weight than

almost any other breed—the two-year-old weth

ers weighing from 25 to 30 pounds per quarter,

and yielding a long and heavy fleece.

The Old Leicester is a variety of the coarse,

long-wooled breeds. On rich pastures they

feed to a great weight; but being regarded as

slow feeders, their general character has either

been changed by crossing, or altogether aban

doned for more improved varieties.

The New or Border Leicester.—Mr. Bakewell of

Dishly, in the county of Leicester, has the honor

of forming this most importart breed of sheep.

He turned his attention to improving the form

of feeding animals about the year 1755. The

exact method he followed in forming his breed

of sheep is not. accurately known, as he is said to

have observed a prudent reserve on the subject.

But we now know that there is but one way of cor

recting the defective form of an animal—namely,

by breeding for a course of years from animals

of the most perfect form, till the defects are re

moved, and the properties sought for obtained.

Though the Border Leicesters have been bred

from the New or English Leicesters, their forms

and chief characteristics are now widely diffe

rent, and they are frequently classed as a distinct

breed. Forty years ago, the ewes of some of the

present flocks of Border Leicesters in Scotland

were then composed of English blood, and rams

from Mr. Buckley of Normantonhill, Leicesters,

and others were regularly purchased to maintain

the desired purity of blood. At that time pur

chasers of rams for crossing began to give larger

prices for sheep of greater size and bone than

those lately imported from the south. There

can be little doubt this increased size and activi

ty were merely produced by the more extended

fields and cooler climate of Scotland ; while the

stock was still fed on pasturage rich enough to

keep them in high condition. The great proper

ties for the farmer of the Border Leicesters, as

they are now called, are their early maturity and

disposition to fatten. They are also of a most

productive nature, three fourths of a flock have

frequently twins, and triplets are common. They

have long open and spiral wool; ordinary fleeces

weigh about eight pounds, but ram fleeces often

reach double that weight.

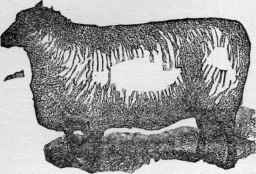

Rocky Mountain Sheep.—All the wild sheep

known are natives of mountainous districts, and

are gregarious. The Rocky Mountain sheep,

called also Big Horn, is famous for its enormous

horns, good quality of meat, and fine wool with

Rocky Mountain Sheep.

here and there, however, long overlapping hairs.

None of the domesticated breeds can be traced

to this variety, but it would, no doubt, readily

cross with any of them.

The Moor/and Sheep of Devonshire—sometimes

termed the Exmoor and Dartmoor—have horns,

with legs and face white, wool long, with hardy

constitution, and are said to be well adapted to

the wet lands which they occupy. Their wool

weighs about four pounds the fleece ; but they

are rather small, and in some respects ill-formed.

The Cheviot breed, deriving their name from the

Cheviot Hills, are longer and heavier than the

Black-faced. Their wool is fine and close ; a

medium fleece weighs about three pounds and a

half to four pounds ; a carcass, when fat, weighs

from 16 to 18 pounds and upward per quarter.

268

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

Their faces are white; their legs are long, clean

and small-boned, and clad with wool to the

hough. Their only defect of form is a want of

depth in the chest; yet, with this exception,

their size, general shape, hardy constitution and

fine wool are a combination of qualities in which,

as a breed for mountain pasturage, they are yet

unrivaled in Scotland, though they require a

larger proportion of grass to heather than

The Black-faced Heath breed, which, being the

most hardy and active of all domesticated sheep,

are the proper inhabitants of every country

abounding in elevated heathy mountains. They

have spiral horns, their legs and faces are black,

with a short, firm and compact body; their wool

is coarse, weighing from three to four pounds

per fleece ; but the improved breed, which is of

mixed black and white in the face and legs,

yields a finer and a whiter wool. They fatten

readily on good pastures, and yield the most de

licious mutton ; the wedder flocks, when three

Black-faced Ewe and Ram.

known to inhabit the most northerly parts of

Europe, from which it is supposed the fine

wooled sheep of the northern islands of Great

Britain and the Highlands of Scotland have

been derived. They are hardy in constitution,

and well adapted to the soil and scanty pastures

on which they are reared, but would ill repay

their cultivation in lowland districts.

REARING AND KEEPING.

Rutting.—The “rutting” is from September till

the middle of December, according to the variety

of sheep and the system of feeding. White-faced

modern breeds have the tups early among them,

and the hill flocks are later. The period of ges

tation is from 20 to 21 weeks.

Lambing Time.—Ewes occupying sown or low-

ground pastures lamb in March, while those not

so well provided for—the mountain sheep—do

not drop their lambs usually till April. The

ancient breeds generally have only one lamb in

a season, but modern highly fed varieties fre

quently have twins, occasionally triplets, but

rarely more. Lambs intended to come early

into the market are as often as possible dropped

in January.

Weaning Lambs.—Generally lambs are weaned

in July and August. Weaning of breeding or

store lambs, however, is a feature of modern

sheep-farming; at one time it was not uncommon

to see several generations persistently following

the parent stem.

Pasture Suitable for Sheep.—The land best suited

for sheep is one that is naturally drained, with a

sandy loam or gravelly soil and subsoil, and

which bears spontaneously short, fine herbage,

mixed with white clover. It should be rolling,

and may be hilly in character rather than flat

and level. Low spots or hollows in which marsh

plants grow are very objectionable and should

be thoroughly drained. One such spot upon an

otherwise good farm may infect a flock with deadly

disease. No domestic animal is more readily

affected by adverse circumstances than the sheep,

and none has less spirit or power to resist them.

It is by long experience that shepherds have

learned that the first requisite for success In the

rearing of sheep is the choice of a farm upon

which their flocks will enjoy perfect health, and

that dryness of soil and of air is the first necessity

for their well being. By a careful and judicious

choice in this respect most of the ills to which

sheep are subject are avoided.

The nature of the soil upon which sheep

are pastured has great influence in modifying’

the character of the sheep. Upon the kind of

soil depends the quality of the herbage upon

which the flock feeds. Soils consisting of de

composed granite or feldspar, and which are rich

years old, are generally fattened on turnips in

arable districts, and weigh from 16 to 20 pounds

per quarter. They exist in large numbers in the

more elevated mountains of Yorkshire, Cumber

land, Westmoreland, Argyleshire, and in all the

higher districts of Scotland where heather is

abundant. Recent severe winters have led to

their re-introduction in high grounds where they

had for a time been supplanted by the Cheviot

and other varieties.

This breed, though not acclimatized in the

United States, is thought by some authorities to

be admirably adapted to our exposed mountain

localities or our unsheltered plains.

The Shetland Sheep inhabit those islands from

which they derive their name, and extend to

the Faroe Islands and the Hebrides. In gen

eral they have no horns. The finest fabrics

are made of their wool, which resembles a fine

fur. This wool is mixed with a species of coarse

hair, which forms a covering for the animal when

the fleece proper falls off, A similar variety is

SHEEP. 269

in potash, are unfavorable for sheep. Even tur

nips raised on such lands sometimes affect the

sheep injuriously, producing disease under which

they waste away, become watery about the eyes,

fall in about the flanks, and assume a generally

unhealthy appearance. Upon removal to a lime

stone or a dry sandstone soil, sheep thus affected

improve at once and rapidly recover. The lambs

are most easily affected, and many are yearly lost

by early death upon lands of an unfavorable

character. As a rule, lands upon which granite,

feldspathic or micaceous rocks intrude, or whose

soils are derived from the degradation of such

rocks, should be avoided. Such soils are, how

ever, not without their uses, for they are excel

lently adapted to the dairy. The soils most to

be preferred are sandstone and limestone lands,

of a free, dry, porous character, upon which the

finer grasses flourish. The soils which are de

rived from rocks called carboniferous, which

accompany coal-deposits or are found in the

regions in which coal is mined, are those upon

which sheep have been bred with the most suc

cess.

Fondness of Sheep for Weeds.—Sheep eat a variety

of vegetation other than the true grasses. They

are fond of many weeds, and if allowed will soon

reduce the weeds that spring up after harvest.

All the pasture grasses are natural to sheep,

except those which close feeding is apt to kill.

Blue grass, orchard grass, the fescues, red-top,

rye grass, etc., may be the main dependence for

sheep; clovers they do not like so well. In pas

turing ewes with lambs it is well to have spaces

through which the lambs can pass, and yet which

will not permit the egress of the ewes. In Eng

land these are called lamb-creeps : this arrange

ment often enables the lambs to get much succu

lent food outside, and they do no damage to

crops. In fact, sheep are often turned into corn-

fields and other hoed crops, late in the season,

to eat the weeds. They will soon clean a crop if

it be such as they will not damage.

Water.—It has been said that sheep require no

water when pasturing. But that is absurd. On

very succulent grass they will live without it, and,

as a rule, take but little. Like any other ani

mal, sometimes their systems require more than

at others. This is especially true during suck

ling time. See that they have it, and of pure

quality. Sheep should never drink from stag

nant pools.

Protection from Insects.—In summer sheep

should have shelter where they may escape from

the insects that torment them, especially the

gadfly, and others producing internal parasites ;

also, during July and August, provide a plowed

surface of mellow soil, and smear their noses,

when necessary, with tar.

Early and Late Pastures.—The better your early

and late pastures are, the easier you can winter

your sheep, especially in the West, where few

roots are raised. Attend to this, and supplement

the pastures by sowing rye and other hardy ce

real grains, which may be done on corn land of

the same season, at the last plowing, and upon

grain land intended for hoed crops next season.

Light grain of little worth will prove very valu

able in this way if sown as directed.

Never allow your sheep to fall away in flesh

before they are put into the feeding yards and

barns for the winter. The time to feed is before

they begin to lose flesh. They will, of course,

shrink somewhat in weight as the feed becomes

dry, but if properly fed it will be chiefly moisture

that they lose. When the full succulence of the

flesh is to be kept up, there is nothing better than

roots—Swedish turnips, beets and carrots being

the most profitable in the West. At any rate, as

the pastures become dry, let the sheep have one

feed a day of something better than they can

pick up in the fields.

Winter Feeding.—You cannot have an even tex

ture of wool if sheep are allowed to fall away

greatly in flesh. Nor can heavy fleeces be raised

on hay. If you do not intend to take the best of

care of sheep, and keep them thriving, you had

better not keep any but the commonest kinds.

Roots are essential to the best care of sheep.

Carrots are excellent for ewes before lambing

time, and parsnips for those giving milk; the

latter may be left all winter in the ground and be

fed up to the time grass becomes flush. Beets

should not be fed until after January, on account

of an acrid principle they contain when first pit

ted. They are best when used after the Swedes

are exhausted.

Marking Sheep.—To mark sheep without injury

to the wool or to the animal, take ½ pint linseed

oil, 2 ounces litharge and 1 ounce lampblack ;

boil all together. Apply the mixture when

needed.

SHEARING.

Previous to shearing, all the sheep should be

collected and washed, to rid the fleece of impuri

ties. After being washed they ought to be driven

to a clean pasture field, and there remain three

or four days before they are clipped. Before

commencing the shearing of sheep, they ought to

be carefully examined, to ascertain whether or

not they are really ready for being shorn. Few

greater errors can be committed in the manage

ment of stock than that of too early clipping.

The practice is highly injurious both to fat and

lean stock, and not only retards their improve

ment, but not unfrequently originates organic

I disease, both acute and chronic.

270

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

It is important that the shearing be properly

done, and no unskillful person should be allowed

to use the shears. May is the usual time for

shearing in the Northern States. The tools

are a pair of shears and a shearing-bench.

The common shears with a thumb-piece upon

one side, and an easy spring, is the best tool

for the shearer. The shears should be brought

to a fine, sharp edge upon a fine oil stone.

The bevel of the cutting edge should be some

what more than that of a common pair of

scissors and less than that of a plane-iron.

The floor of the sbearing-room should be kept

free from straw, chaff or litter; and if a boy be

kept at work removing dirt, tags and rubbish,

his time will be well employed. In shearing,

the shearer catches the sheep by the left hind

leg, backs it toward the bench and rolls it

over upon it. He then sets the sheep on its

rump, and standing with his left foot upon the

bench, lays the sheep‘s neck across his left knee,

with its right side against his body. The two

fore legs are then taken under the left arm, and

the fleece is opened up and down along the

center of the belly by small short clips with the

shears. The left side of the belly and brisket are

then sheared. The tags are clipped from the

inside of the hind legs and about the breech, and

thrown upon the floor. They should be swept

up at once and gathered into a basket, and not

allowed to mingle with the fleece-wool. The

breech is then shorn as far as can be reached.

The wool from the point of the shoulder is then

clipped as far as the butt of the ear. The wool

is shorn around the carcass and neck to the fore-

top, proceeding down the side, taking the foreleg

and going as far over the back as possible, which

will be two or three inches past the backbone.

When the joint of the thigh (the stifle) is

reached, the shears are inserted at the inside of

the hough, and the wool shorn around the leg

back to the thigh-joint. The wool over the rump

is then shorn past the tail.

The sheep being now completely shorn on

one side, and two or three inches over on the

other side, along the back from neck to tail, is

then taken by the left hind leg, and swung

around with the back to the shearer, leaving

some wool beneath the left hip, which will ease

the position of the animal and keep it more

quiet. The wool is then shorn from the head

and neck down the right side, taking the legs

and brisket on the way. The fleece is now

separated. The job is completed by clipping

the tags and loose locks from the legs.

When the sheep‘s skin has been unavoidably

cut in shearing, each cut should be smeared with

tar, which will prevent flesh flies from depositing

their eggs in the wound, and probably avoid

after-trouble.

Tying the Wool.—The fleece should be as little

broken as possible in shearing. It should be

gathered up carefully, placed on a smooth table,

with the inside ends down, put into the exact

shape in which it came from the sheep, and

pressed close together. If there are dung-balls,

they should be removed. Fold in each side one

quarter, next the neck and breech one quarter,

and the fleece will then be in an oblong square

form, some twenty inches wide and twenty-five

or thirty inches long. Then fold it once more

lengthwise, and it is ready to be rolled up and

tied or placed in the press.

DISEASES OF SHEEP.

Diseases in sheep are not numerous, in com

parison with the maladies of other domestic ani

mals, but they are severe; one of the worst being

Scab, a kind of itch, arising from an insect in

the skin, and peculiarly destructive. The dis

eased animal seeks to relieve itself of an intoler

able itching by rubbing against every projection;

and wherever it rubs, the icarus remains to carry

the infection through the flock. Sometimes a

malicious sheep-owner will let a scabby sheep

run at large over ground occupied by a neighbor,

and the consequences may be ruinous.

Treatment.—Take sulphur, 2 ounces; pow

dered sassafras, 1 ounce; honey sufficient to

make a paste. Dose, a tablespoonful every morn

ing. If a few doses do not remove the trouble,

take 4 ounces fir balsam and 1 ounce sulphur,

mix thoroughly, and anoint the sores daily.

Foot-rot customarily makes its appearance in

flocks ill cared for—allowed to graze on poorly

drained lands. The sheep suffer greatly, and

fall into poor condition otherwise. A good

shepherd knows the consequences that must, in

a majority of cases, follow perseverance in feed

ing over ill-drained meadow or swamp: but some

times that cannot be avoided.

Treatment.—Remove to better conditions as

soon as possible, and apply to the affected feet a

preparation of tobacco, which tones up the dis

eased members. Foot-rot will always yield to

treatment if taken in time.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |